Introduction

The LASA 2026 Call for Papers invoked the republican tradition and its revolutionary implications as a way to foreground the underappreciated contributions of Latin America and the Caribbean to global transformations that have occurred over several centuries. These transformations, which continue to shape the contemporary world, entail what Guillermo O’Donnell (1998, 113) called an “uneasy synthesis” of republican, liberal, and democratic thought and action. Although each taps into pre-modern undercurrents, springing from ancient Greek, republican Roman, and medieval sources, they nonetheless crystallized in the institutions and practices that emerged out of the Glorious Revolution, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, the insurrection of Tupac Amaru II, and Hispanic-American struggles for independence.

It was in the Americas that the revolutionary and republican traditions assumed their specifically anti-colonial characteristics, generating an especially uneasy synthesis. The legacies of revolutionary, egalitarian, and democratic struggles—and their antitheses, counter-revolution, authoritarianism, oligarchy, and neocolonialism—continue to work themselves out. For that reason, we take a depiction of the exodus from Jujuy as emblematic for LASA 2026. It represents emancipation, the formation of a people, and the movement away from monarchy; it also captures social inequalities, ethnic hierarchies and violence, and patriarchal domination (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. El Éxodo Jujeño (detail).

Source: Anonymous, mid-20th century painter. Provincial Historical Museum of Jujuy.

Photo courtesy of Rubén Antonio Cortez.

Republicanism, Liberalism, and Revolution in Independent Latin America

Starting in Haiti and, belatedly, including Brazil, republicanism emerged as a shared project of the Americas. It combined a commitment to popular sovereignty and, in a crucial discontinuity with colonial rule, secularism, and liberalism. In this fecund period, in which ties with the metropolis were radically severed, diverse constitutional alternatives were proposed. From Manuel Belgrano’s “Inca Plan,” which would have restored dynastic rule under the Tupac line, to Simón Bolívar’s mixed constitutional proposals, independence revolutions entailed difficult battles of arms and ideas.

In “El desafío republicano de Hispanoamérica,” Hilda Sabato describes how historical research has found in Spanish America a great laboratory of republican experimentation which deserves to be appreciated, not as a failure relative to an abstract or idealized Eurocentric standard, but as part of the inevitably turbulent processes of territorial and institutional change that accompanied the struggle for independence from colonial rule. In this context, the adoption of popular sovereignty as a principle of legitimation and way of life was a radical—indeed revolutionary—change, even if its institutional forms proved incomplete, reversible, contested, and unstable. At the same time, and in contrast to classical democracy, the idea of the republic implied a marked distinction between government and the people, ruler and ruled. The republican form of government was based on representation: popular assemblies and town councils (cabildos abiertos) gave way to legislatures and parties.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere, what made emerging republics democratic—or not—was the degree to which representation was inclusive. Here, perhaps, a brief conceptual excursus is necessary. What we today call democracies are, in fact, democratized republics. A republic is government by representation, with protection for the liberties of its citizens made possible by the separation of powers and the rule of law. Initially conceived as an alternative to democracy and monarchy, republicanism was democratized as the rights and freedoms of citizens were extended to all, constituting what Guillermo O’Donnell called the “full institutional package of polyarchy.”

Embracing republicanism as an alternative to monarchy set Latin America on a radical new trajectory. In many cases, manhood suffrage was extensive, at least for the times; competitive elections were accepted as the source of legitimacy; public opinion played a role in shaping policy and legislation; and constitutions were written with the intent of guaranteeing civil and political rights. And yet these were not egalitarian republics: women, for example, were not given the vote, nor were they able to fully participate in the public sphere; and Indigenous peoples lost some of the protections provided by colonial arrangements. Although early independence thinkers like Simón Rodríguez advocated a radically egalitarian and even a prototypically social democratic version of liberalism, over time, as Leandro Losada notes in “Republicanismo, liberalismo y democracia en el pensamiento político hispanoamericano”, a less democratic and more technocratic conservative-liberal synthesis won out. By the end of the 19th century, oligarchic states were consolidated under the leadership of elites occupying positions of power rooted in hierarchies of class, gender, and ethnicity.

The Persistence of Oligarchy in Contemporary Republics

In the oligarchic states of the 19th century, a small set of traditional economic elites, often associated with foreign interests, directly dominated the political system. Conventional wisdom suggests such states were superseded by the rise of populism and democratization of the first half of the 20th century. Nevertheless, oligarchic modes of rule continued to coexist with democracy (Foweraker 2020, 3-5). The persistence of vast disparities in wealth and income in Latin America posed a major challenge to the fulfillment of the revolutionary implications of republican principles. The fusion of power and wealth, although compatible with competitive electoral regimes, weakened both democratic representation and state capacity.

As a lens for understanding history, republicanism brings inequality into focus as a major—if not the major—problem of Latin American politics. High levels of inequality place some citizens in a position of vulnerability and dependency on others. Latin American republics “are not very republican,” writes Alberto Vergara (2023, 230) in Repúblicas Defraudadas, because citizens are subject to discrimination, social segregation, and lack of access to public goods. In “Democratic or Republican Backsliding?” Vergara contrasts democratic backsliding, in the political regime, with republican backsliding. The latter is typically the precursor of the former, as the encroachment of the executive on other branches of government and the weakening of horizontal accountability lay the groundwork for the assault on democracy’s core electoral institutions. Republicanism depends on a lawful state capable of upholding the rights and freedoms of citizenship.

Today, as in the 19th century, patrimonial conceptions of power are inimical to representative government. Drawing on Max Weber, Jan Boesten in “The Patrimonialization of State Coercion” defines the patrimonial state as one in which the exercise of power by the ruler does not distinguish the public and private spheres. The state itself is regarded as the personal property of the ruler, which is analogous to the way patriarchal domination operates in the domestic sphere. It is personal loyalty, not impersonal norms, that rules the roost. Without robust bureaucratic institutions, including autonomous agencies and staff recruited on meritocratic grounds, effective representation is undercut by low-intensity citizenship and the paternalism of personal rule.

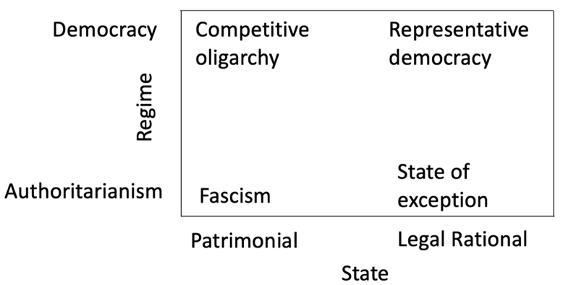

Combining the distinction between patrimonial and bureaucratic states with that between democratic and authoritarian regimes yields four distinct categories. Representative democracies require legal-rational bureaucratic states and democratic regimes. The state of exception occurs when democracy is suspended within a legal-rational state. In patrimonial states, the crisis of representation—typically caused by a lack of programmatic parties, the weakness of legislatures, and the absence of the rule of law—can produce competitive oligarchies in which oligarchic modes of rule and populist mobilization oscillate. A simultaneous assault on democracy and the legal-rational state tends to lead to fascism.

Table1. State and Regime in Latin America

The right-hand side of this box shows regimes using terms that are normatively acceptable in our times. Nayib Bukele does not present himself as a fascist, but as a “cool” dictator, someone who has imposed a state of exception in order to protect society, and with the backing of the public. Likewise, most electoral democracies in the Americas stylize themselves as representative democracies, even though many of them are better described as competitive oligarchies. Rulers who take a chainsaw to the bureaucracy may win temporary plaudits from the right-wing spectrum of opinion, but they undermine representative government in the process.

Each variation on the left-hand side of the table represents potential corruptions of the republic. As several contributors note, concern for corruption is at the heart of republican thought—not just bribery and nepotism, but political rot or decay. Republican corruption—or, better, the corruption of the republic—includes failures in all those spheres vital to self-government: representation, fundamental rights and freedoms, the rule of law, and the separation of powers. When these features of self-government are compromised, they are easily replaced by oligarchic modes of rule, so that the wealthy few are able to exercise power for their own benefit.

A good example of an oligarchic mode of rule is state capture, which is the theme of “Economic Elites and Oligarchic Modes of Rule in the Andes” by John Crabtree and Jonas Wolff. Highly concentrated economic wealth of the sort that characterizes the Latin American variety of capitalism, and the presence of neo-patrimonial states, virtually guarantees the prevalence of oligarchic modes of rule. They were standard practice in the 19th century, but they persist in the present. Indeed, the neoliberal model of development has contributed to intensifying oligarchical tendencies in contemporary polyarchies. This does not mean that the polyarchic regimes in the region are not competitive, but electoral democracies in neo-patrimonial states can best be described as “competitive oligarchies” (a term used by Dahl, 1971).

The Struggles against Oligarchy

Republic and revolution are not antitheses, nor is the persistence of oligarchical tendencies passively accepted by all political actors. As Valeria Coronel shows in “Leer la Revolución y el Republicanismo democrático desde América Latina,” plebeian and indigenous radical republican revolutionary projects often re-emerge in moments of crisis generated by capitalism. These alternative projects can reinforce democratic and republican values, even as they disrupt institutional arrangements, by seeking to accommodate plebeian participation in politics. In Latin America and the Caribbean, radical republicanism has indigenist, anti-colonial, anti-patriarchal, and anti-oligarchic features beyond the Eurocentric limitations of liberalism. Whereas republicanism in the north western quadrant of the world represents a response to the perception that liberalism, at its best, crowds out the shared ethical-political community that republicans value, in the south western quadrant, liberalism is weaker and oligarchic power poses the greater threat to the common good—including the civic community itself.

Is it possible to imagine a popular form of republicanism that is not the same as populism? Populism appeals to the idea of the people as an identity constructed in opposition to the power of an oligarchy. As a reactive force, it seeks to replace the tyranny of the minority with that of the majority, regressive with progressive redistribution, and bossism (gamonalismo, coronelismo) with democratic Caesarism. Although populism can be a powerful and progressive force for inclusion, it fails to address—and indeed it typically exacerbates—the politicization of the state apparatus, the reliance on spoils rather than laws, and the centralization of power rather than its diffusion. Popular republicanism, by contrast, might address the unfulfilled promise of republicanism at its origins, strengthening representation, protecting the rights and freedoms of all citizens equally, and upholding the rule of law through the constitutionally legitimate exercise of constituent power.

The persistence of oligarchic modes of rule has often corrupted Latin American democracies, as argued in “Systemic Corruption, Oligarchic Democracy & Plebeian Republicanism” by Camila Vergara. She uses the term “systemic corruption” to capture the ways in which Latin American states, especially in their judicial, legal, and regulatory capacities, systematically benefit the powerful and rich at the expense of the many. The term oligarchic “decay” aptly captures the meaning of corruption in this case. It is about the distortions of the public purpose of institutions that prevent them from functioning democratically—a feature, not a bug, of oligarchic democracy. How can oligarchy be balanced? Historically, whether in ancient Greece or republican Rome, the answer has been by reinforcing plebeian features of politics, which is the approach recommended—and studied in detail—by Vergara. We may reimagine constitutions through a plebeian lens.

What model of development is attached to the oligarchic mode of rule? In “Movimientos populares frente a la oligarquización plutocrática,” Federico M. Rossi calls attention to the growing fusion of the economic and political spheres in the neoliberal era. The double transition to market economics and liberal democracy has revived plutocratic politics. This is a non-consolidated, even recursive process that, in Rossi’s view, forms part of the dispute between coalitions of actors struggling to reduce or expand the sociopolitical arena, which is a key dynamic defining Latin American history. Through estallidos sociales (social explosions), territorialized popular movements have posed the “social question” in ways that disrupt plutocratic politics, generating resistance to oligarchic control, which can (in some cases) lead to alternative coalitions to expand the sociopolitical arena.

The last three articles in this dossier—dealing with plebeian and indigenist revolutionary (Valeria Coronel), plebeian constitutional (Camila Vergara), and territorialized social movements (Federico Rossi)—prefigure historical popular projects that pose possible alternatives to the patrimonial state and oligarchic democracy in Latin America.

Republic, Oligarchy, and Revolution Reconsidered

Words, like muscles, atrophy with disuse. In concluding, we explain our use of the concepts republic, oligarchy, and revolution. We have focused on these terms with the goal of encouraging their usage among members of our scholarly community. Reviving them helps reframe the current debate on democratic backsliding, crises of democracy, and the spread of illiberalism.

A widely accepted framing of the current crises of democracy emphasizes the challenge posed by populist authoritarians to liberal democracy. This is an important subject for debate, but we insist that populism is almost always a response to oligarchy, a term that has fallen into disuse among mainstream social scientists. The dialectical relation between populism and oligarchy reflects the centrality of inequality in contemporary politics. When people embrace demagogues, we should ask at least two questions.

The first question concerns the material foundations of democracy. Do inequality, lack of opportunity, barriers to social mobility, or the widespread sense of being left behind in an era of neoliberal globalization contribute to our democratic malaise? The second question concerns the civic community. Have we lost a shared understanding of the common good? Neoliberalism was a concerted assault on both the material and civic sources of democratic stability: it contributed to the rise of inequality while casting shade on the very idea of the common good. In the face of this, elected leaders in liberal democracies have proven at times remarkably complacent, if not overtly supportive, of the very processes that have given rise to extreme concentrations of wealth and power and the erosion of civic community.

Indeed, liberal democracy has been predicated upon a passive approach to citizenship that is insufficient for its own preservation. Liberalism provides reasons to appreciate the sanctity of property rights, meritocratic recruitment and promotion, technocratic and managerial forms of governance, and the primacy of the private sphere. But insistence on the sanctity of private property can undermine an appreciation for the historic bargains that are the source of settled property rights. Meritocracy can be a source of inequality when those who possess it do so by virtue of unearned privileges. Technocratic and managerial solutions to policy problems often involve outsourcing moral judgments to market and bureaucratic forces, thereby undermining civic virtues and community. And the private sphere can impoverish the public sphere when the satisfaction of individual wants and needs comes to supersede the collective requirements of republican self-government.

What is more, we reiterate that liberal democracy itself is but democratized republicanism—or, more exactly, representative government with fully inclusive citizenship. This means that democracy cannot be easily disentangled from republican practices and institutions like representation, the separation of powers, and the rule of law, nor can it be practiced as a system of self-government without a particular kind of state apparatus that insulates politics from corrupting forces arising in the private sphere. This is why the threat of populist authoritarianism is often perceived through a distorted lens: we focus much of our concern on the threats to individual rights and freedoms while neglecting to call attention to the destruction of the state capacity that guarantees those very rights and freedoms.

Why do we write of revolution? Revolutions may be considered convulsive and episodic events, like the French Revolution, the Mexican Revolution, the Russian Revolution, or the Cuban Revolution. These extraordinarily important and invariably violent processes are like earthquakes: they are dramatic and unpredictable shocks to the status quo. But revolutions can also be understood as large, slow, long-term historical processes (Tilly 1995). That is the sense in which we speak of the Atlantic revolutions, including republican founding in the Americas—not just the often violent moments in which decisive battles were fought, but also the complex social changes that lay the foundation for new states, regimes, and patterns of citizenship over many centuries.

Contemporary democratic republics are the culmination of long historical processes, encompassing struggles for independence, the consolidation of nation-states, the expansion of the sociopolitical arena, and resistance to neoliberalism. Reframing our comprehension of these long-standing republican trajectories is the goal of this LASA Forum.