From September 14, 2024 through March 15, 2025, the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona hosted the first major retrospective of the works of Louis Carlos Bernal. Known as “the father of Chicano fine art photography,” Bernal focused his lens on the private and public spaces that defined Chicano life in the borderlands (Guevara Golden 2025, ii). The exhibition, Louis Carlos Bernal: Retrospectiva, “included more than 100 photographs and archival materials related to Bernal’s career” and was accompanied by a corresponding book, Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía, “the first major comprehensive analysis of Bernal’s life and work by curator and writer Elizabeth Ferrer” (ii). Together, the exhibition and monograph reintroduced Bernal, who passed away tragically in 1993, to a contemporary borderlands audience.

In this short essay, I propose that Bernal’s borderlands photography, despite its realist underpinnings, encapsulates the speculative possibilities of Borderlands 2.0. Building on the work of Catherine S. Ramírez, Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson, B. V. Olguín, and William Calvo-Quirós, I suggest that Borderlands 2.0’s speculative cultural production reorients time and space to make visible alternative genealogies of borderlands survival. To illustrate this point, I turn to Bernal’s Benitez Suite (1977), a set of seven black-and-white photographs that transcend temporal and spatial divisions to center borderlands life over and against the forces that would seek to destroy it.

1. Louis Carlos Bernal: Borderlands Photographer

Louis Carlos Bernal was a son of the borderlands. He was born in 1941 in Douglas, Arizona, the U.S. sister city to Mexico’s Agua Prieta, Sonora. After spending his initial years in Douglas, when he was six years old his family moved to Phoenix, Arizona. It was there that Bernal discovered his love of the camera, eventually studying photography at Arizona State University, first as an undergraduate and later as an MFA student. When Bernal completed his studies in 1972, he moved with his family to Tucson, Arizona, where he was hired to establish the photography department at Pima Community College. He remained in Tucson until his untimely death in 1993 (Ferrer 2024, 26).

Though Bernal’s educational and career trajectory were firmly anchored in Arizona, his photography took him across both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. In the U.S., Bernal photographed urban and rural Mexican-American communities throughout California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. He was especially interested in domestic spaces, often photographing people in their homes. He brought that same intimate perspective to his photographs of public spaces, depicting the daily lives of borderlands communities in a range of environments from bars to barbershops. In Mexico, Bernal found the intellectual and artistic community he felt he lacked in the U.S. Working at a time when there were few Chicano photographers, Bernal found more kinship with Mexican artists, with whom he collaborated and maintained close friendships throughout his career (Ferrer 2024, 41-42).

Bernal began his career as an artist against the backdrop of the Chicano movement, rooting his work in a commitment to social justice. Though Bernal was an art photographer, he was heavily influenced by Chicano documentary photography, which captured scenes of protest from farmworker strikes to student walkouts. As Elizabeth Ferrer observes, “when Louis Carlos Bernal peered into the lives of common Mexican-American people, he was drawing from the same well of empathy and deep desire for social justice that informed the pioneering generation of civil rights photographers, to give visibility to those with little agency and to conjure histories and traditions that have been subject to political and cultural erasure” (30).

For Bernal, what he called “Chicanismo” was central to his artistic practice. He explained:

Mexican-American is the term used to describe a person who is of American birth but whose cultural soul derives from Mexico. This dual reality has been a burden which has clouded our identity. Chicanismo allows us to accept our history but also gives us a new reality to deal with the present and the future. To be a Chicano means to be involved in controlling your life. Chicanismo represents a new sense of pride, a new attitude and a new awareness . . . The Chicano artist cannot isolate himself from the community but finds himself in the midst of his people creating art of and for the people. My images speak to the religious and family ties that I have expressed as a Chicano. I have concerned myself with the mysticism of the Southwest and the strength of the spiritual and cultural values of the barrios (qtd. in Ferrer 2024, 27).

This mystical collapsing of time and space, from a “dual reality” to a “new reality,” aligns with Gloria Anzaldúa’s conceptualization of a mestiza consciousness as described in her seminal text Borderlands/La frontera (1987). As contemporaries, both Bernal and Anzaldúa tapped into the creative possibilities that borderlands, both material and immaterial, held.

In Bernal’s case, he explored the contradictions, complexities, and possibilities of the borderlands by combining a variety of photographic styles. As Ferrer explains, Bernal “meld[ed] documentation with portraiture, still life, and elements of staged photography” (Ferrer 2024, 31). Nevertheless, Bernal was adamant that his “work [was] not documentation in the technical sense, there are elements of it there, but basically my work is my own viewpoint about a particular set of circumstances or conditions that people live under, and their emotions as they react to that” (qtd. in Ferrer 2024, 31). This more-than-documentation approach is strongly displayed in Benitez Suite, which is a powerful challenge to the erasure of borderlands communities from the physical and representational landscape.

2. Benitez Suite: El futuro anterior of Borderlands 2.0

Bernal’s Benitez Suite includes seven black-and-white photographs taken in 1977 in the abandoned home of Mary Benitez. Bernal would often spend significant amounts of time walking a neighborhood and talking to its residents before taking any photographs (Ferrer 2024, 31). In the case of the Benitez Suite, writer Leslie Marmon Silko, a close friend of Bernal’s, explains how he gained access to the home:

One day he was out walking with his camera when he came across a small adobe house. Something about the old house, some presence, caught his attention and he took a closer look. He noticed the door wasn’t entirely shut and when he approached and called out to anyone inside, he was able to look through the crack. He saw thick layers of dust and spider webs and realized the house had not been occupied for a long time; yet nothing had been disturbed. Everything appeared to be just as someone left it long ago, someone who intended to return but never did. Lou went next door and knocked to learn who he might contact for permission to enter and photograph inside the house. As it happened, the man who answered the door was the former occupant’s adult son.

Now this is the wonderful part of the story—something which occurred again and again with Lou—he could wander through a neighborhood and chat with people in their yards or knock on a stranger’s door and immediately win the people’s trust and cooperation. The man told Lou his mother got up one morning and went to her doctor’s appointment and never returned. She was alive but in a nursing home, so her children left her house as she’d left it—the cup and plate on the kitchen table, the bed sheet turned back, a faint imprint of her head on the pillow. The series of photographs became a portrait of a woman we never see but who is not absent either; her essence remains in the house even as she sits in a nursing home. Entities abide in the realm between light and shadow where they shimmer into the present realm only for the split second of the lens shutter before they are hidden again—Lou showed us their luminous traces in our midst—whether we believe or not (Marmon Silko in Simmons-Myers 2002, 29, emphasis mine).

In her description of Bernal’s images, Marmon Silko highlights the temporal shapeshifting of Benitez Suite, which is characterized by an irresolvable in-betweenness. Mary Benitez is not shown, but she is also not absent. The “luminous traces” of her life that Bernal captures tell a story of impossible permanence.

Because the images obscure the boundaries that divide the past from the present and the real from the imagined, I propose approaching Benitez Suite as a speculative work. Building on Catherine S. Ramírez’s conceptualization of Chicanafuturism, Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson and B. V. Olguín define “Chican@ and Latin@ speculative arts” as texts that blend as well as exceed “the discrete generic bounds of sci-fi and fantasy…to obscure colonialist boundaries between self and other, between the technologically advanced and the ‘primitive,’ between the human and nonhuman, and between the past and future” (135). William Calvo-Quirós adds, “the study of Chican@ speculative arts gives us tools to recognize the power of the fantastic, the phantasmagoric, and the imaginary as unique instruments for the pursuit of emancipation, dignity, and social change” (157). Here I focus on three images from Benitez Suite, all of which emphasize space and time to assert a borderlands speculative posture that undermines easy binaries and imagines new pathways for survival.

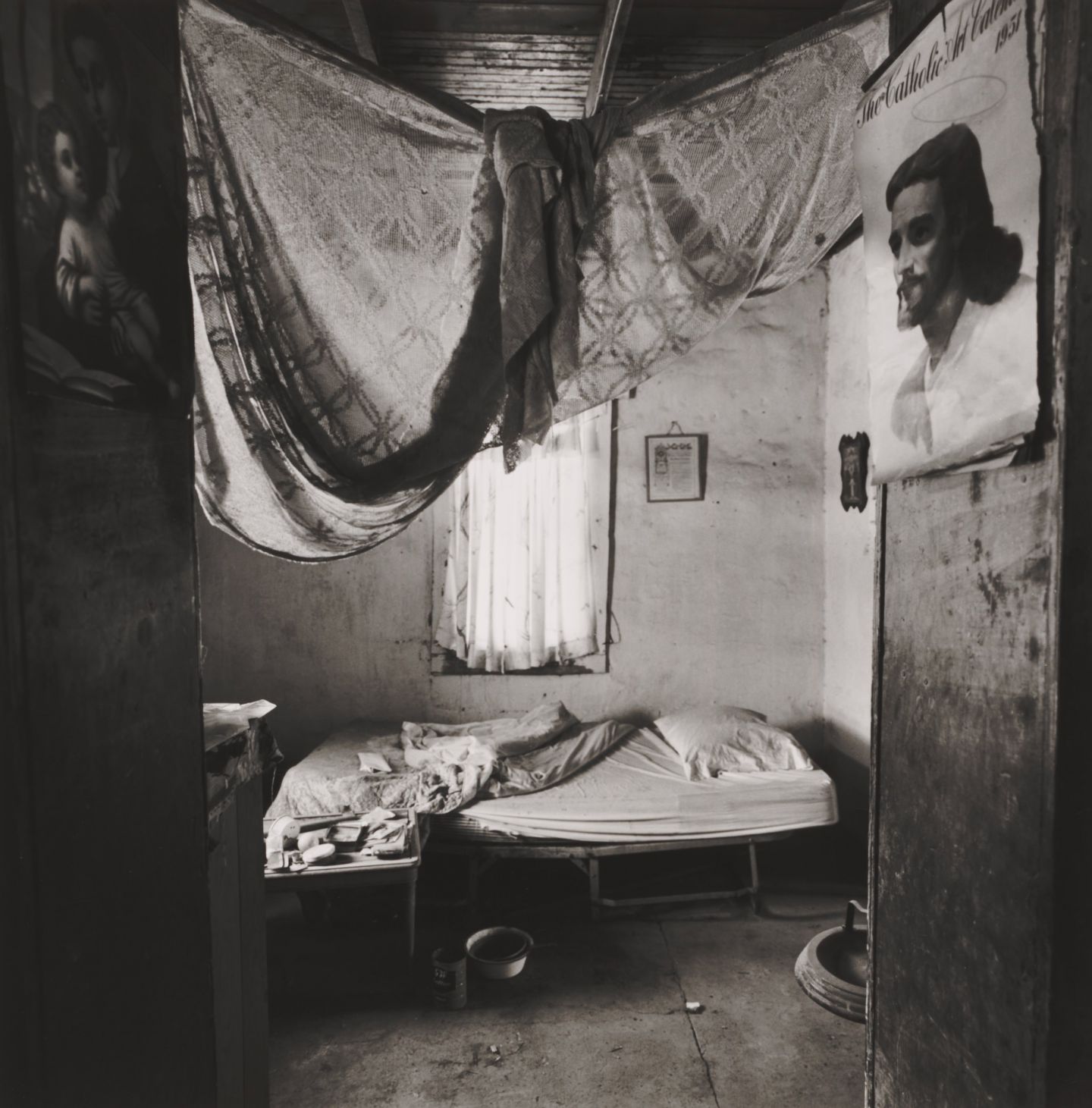

Two of the images, Calendario and Cortina de vestido, introduce the viewer to the space of Mary Benitez’s home. Calendario, so named because of a 1951 Catholic Art Calendar hanging on the wall, depicts Mary Benitez’s bedroom.

Fig. 1 Louis Carlos Bernal, Calendario, 1977, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal.

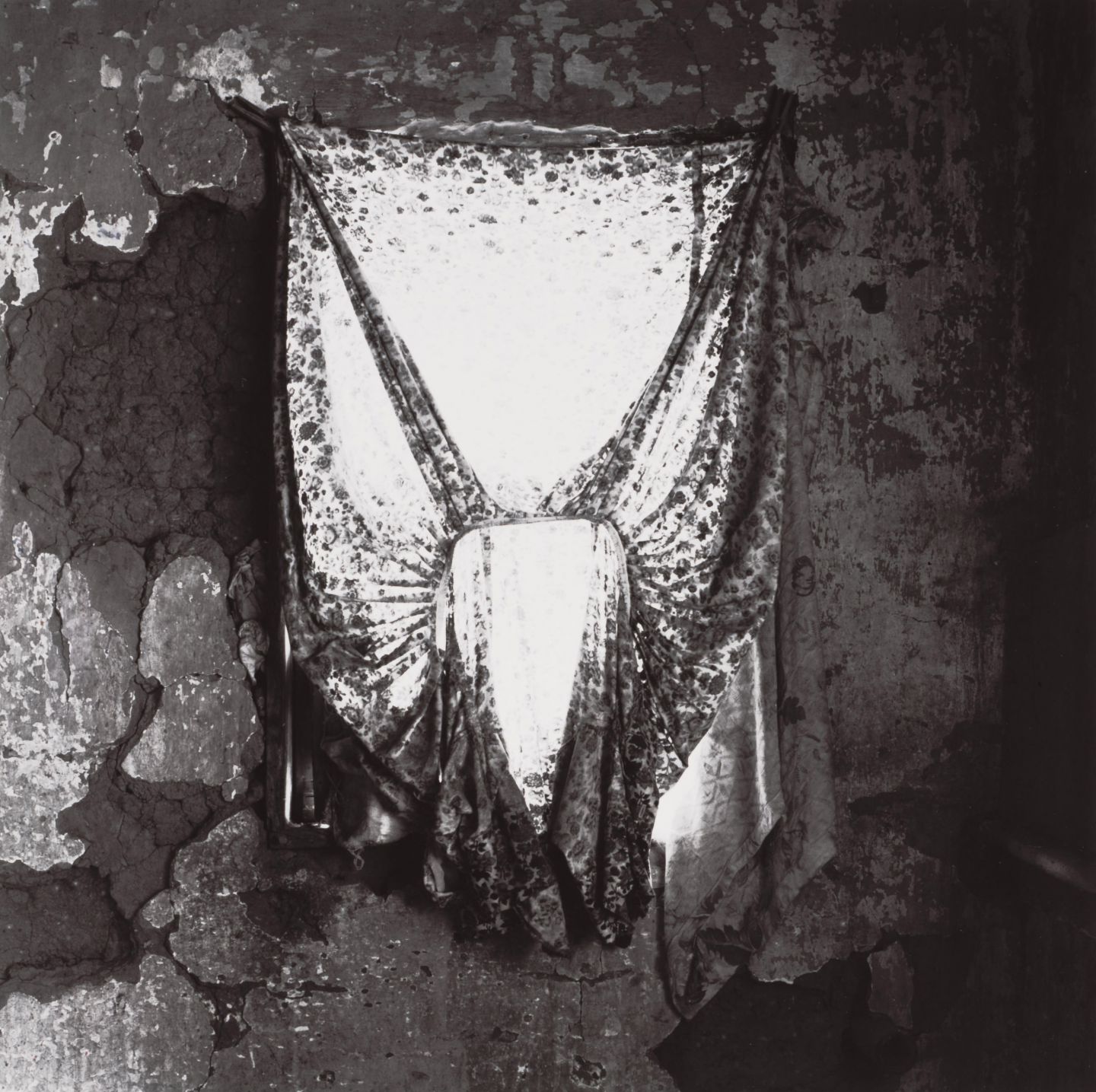

In the foreground, a curtain is draped on itself, functioning as an open door that gives the viewer access to the bedroom that lies behind it. At the center of the room there is a bed with the sheets neatly pulled back as if someone has either just left or will soon return to its small frame. Just to the side of the bed is a window, which allows in the natural light that bathes the scene. The calendar shows a smiling Jesus whose gaze overlooks both the space and the viewer. Cortina de vestido similarly plays with light and dark but shifts perspective to a close-up of a makeshift curtain created by a dress hanging over a window.

Fig. 2 Louis Carlos Bernal, Cortina de vestido, 1977, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal.

The dress is draped perfectly symmetrically, the light filtering through its small repetitive pattern in a way that resembles stained glass. The soft light smooths the rough, flaking walls that surround the window. The image is ordered, serene, and undeniably beautiful. Bernal described his process, reflecting, “I would say my work is reverent. I find something the way it ought to be and preserve it” (qtd. in Simmons-Myers 2002, 9). This reverent approach is palpable in these two images. Together, Calendario and Cortina de vestido seek the splendor within Mary Benitez’s humble home.

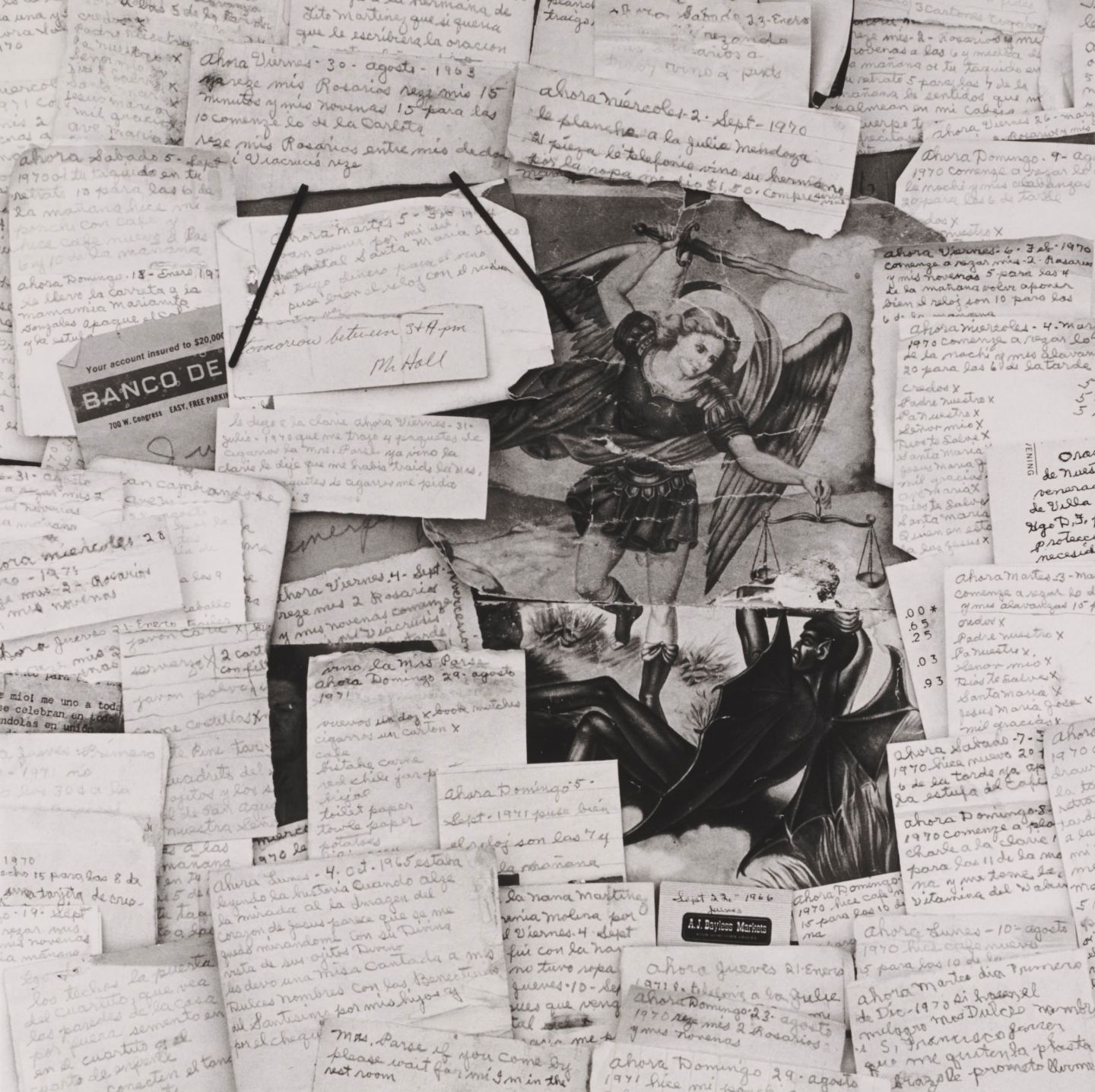

In addition to finding splendor within space, Benitez Suite also remixes time, especially in the aptly named image Ahora.

Fig. 3 Louis Carlos Bernal, Ahora, 1977, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive. © Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal.

Here, Bernal stages a series of notes he finds scattered throughout the home, most of which start with the word “ahora.” Bernal then carefully layers the notes on top of a tattered depiction of the Archangel Michael slaying the Devil. The heavenly being holds a sword in one hand and scales in the other, a common portrayal of the judgement of one’s eternal soul through the weighing of good versus evil deeds. The juxtaposition of the extremely banal everyday tasks in the notes with the apocalyptic grandeur of the religious imagery undermines the easy division between what does and does not matter and what will and will not endure in this life and whatever is to come. The tone of the image is one of urgent irony, a need to define the “now” of a home that is simultaneously frozen in the past while facing an uncertain future.

When put in the context of urban renewal efforts in Tucson at the time, the political stakes of rendering Benitez Suite with an insistence on its present-day beauty become clear. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Tucson was consumed with conversations about urban renewal in the city’s historic center. As Lydia Otero argues in her book La calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City, in downtown Tucson, boosters and real estate developers clashed with longtime Mexican-American residents over “conflicting visions of the past Tucsonans wished to celebrate and the future they hoped to construct” (127). Pro-development politicians and city officials used the rhetoric of blight to malign homes like Mary Benitez’s, reinforcing their narratives through policies that disenfranchised Mexican American communities. As Otero explains,

Public statements by city officials denigrating the appearance of buildings and physical conditions in the neighborhoods in and around la calle conveyed the clear impression that their eventual destruction was an inevitable part of the natural order of things. In 1964, two years before voters approved urban renewal, media reports indicated that city officials had curtailed collection of trash and refuse, reinforcing and reinscribing perception of la calle as a "filthy" place. A woman with a large trash pile behind her house apologetically told reporters, "I’ve called and asked [the city’s sanitation department] to take it away, but they never seem to get here" (101).

Though Mary Benitez’s home was just outside the area that was demolished as part of the city’s urban renewal campaign, its portrayal nevertheless evokes the highly polarized rhetoric about Mexican-American barrios. By countering blight with beauty, Bernal’s images contest the official history not only of Tucson’s downtown, but of all borderlands communities whose histories have been denigrated and destroyed.

3. Coda

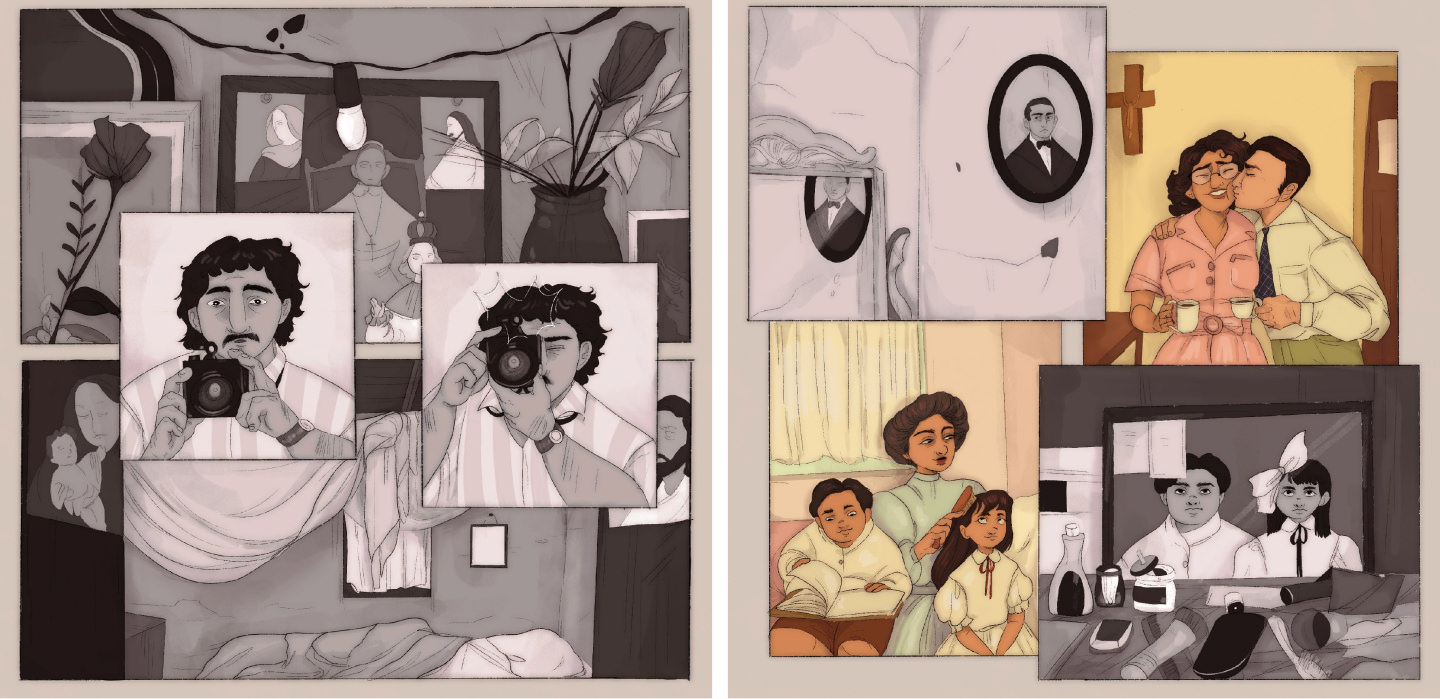

In conjunction with the Bernal book and exhibition, the Center for Creative Photography also produced a zine titled Louis Carlos Bernal: Recuerdo. The zine contains archival materials like newspaper clippings and notes alongside original comics commissioned to celebrate Bernal’s legacy. Arizona-based artist Olivia Morey’s comic, “Recuerdo: Bernal y Benítez / Remembrance: Bernal and Benítez” illustrates the creation of Bernal’s Benitez Suite.

Morey’s first two-page spread mirrors Bernal’s photos themselves.

Fig. 4 Olivia Morey, Panel 1, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

Fig. 5 Olivia Morey, Panel 2, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

In the same black-and-white register, Morey allows us, the viewer, to witness Bernal witnessing this abandoned yet lovingly cared for domestic space. On the second two-page spread, we witness Bernal shift from viewer to creator, snapping pictures of the interior, including pictures inside the Benitez home.

Fig. 6 Olivia Morey, Panel 3, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

Fig. 7 Olivia Morey, Panel 4, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

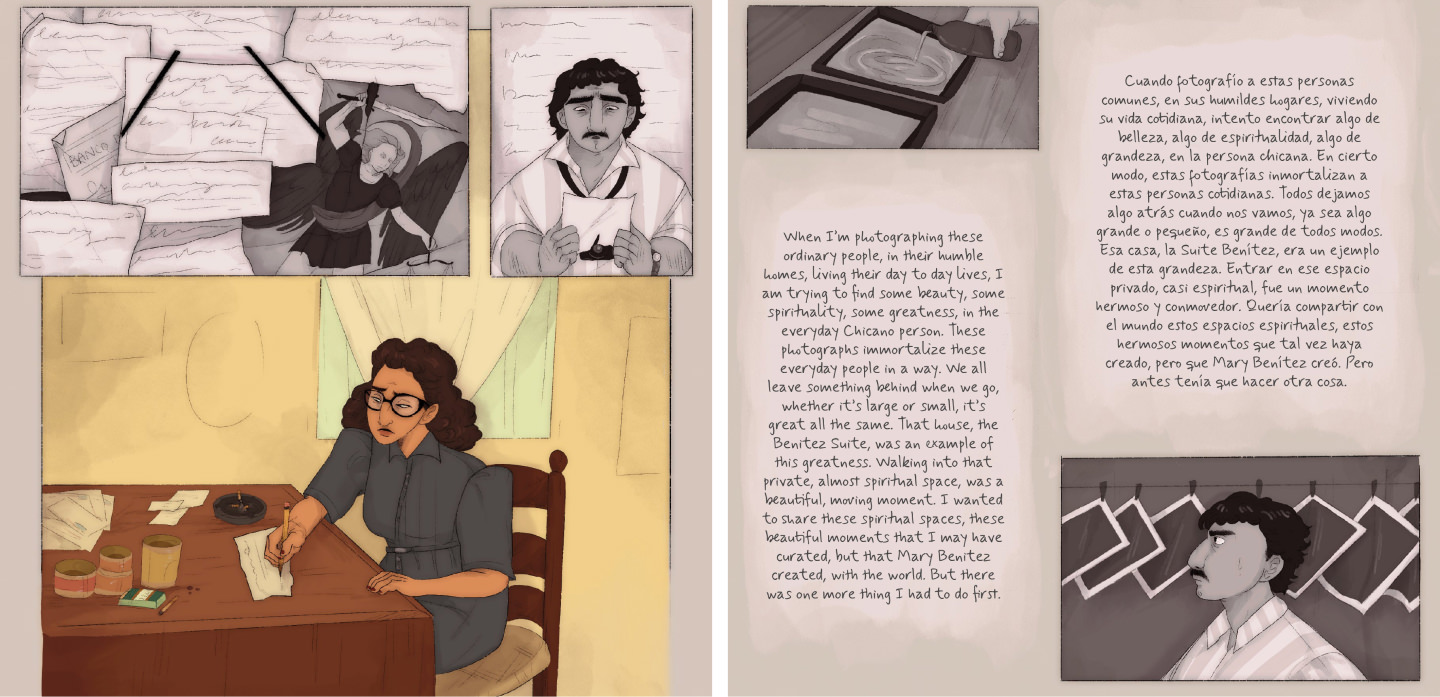

In a striking contrast to the other frames, Morey provides colorful recreations of the original scenes in the pictures. In vivid yellows, pinks, and blues, a young Mary Benitez comes to life alongside what appear to be her husband and children. On the next two-page spread, a young Mary Benitez again colorfully fills the page, this time at her writing desk composing her “ahora…” notes.

Fig. 8 Olivia Morey, Panel 5, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

Fig. 9 Olivia Morey, Panel 6, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

The final two-page spread depicts Bernal with the elder Mary Benitez in her nursing home.

Fig. 10 Olivia Morey, Panel 7, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

Fig. 11 Olivia Morey, Panel 8, Remembrance: Bernal and Benitez, based on the Benitez Suite photograph series, 2025, www.oliviamoreyart.com.

Just as he did in real life, Bernal shows her the images he took in her home. In Morey’s reimagining, as the elder Benitez reviews the images, the colorful memories flood her mind. The final frame shows the color bleeding from her memories in the past to her present in the nursing home, a soft yellow light illuminating her as she is seated next to Bernal, his photos in her hand.

Chicano artist Luis Jimenez wrote of his close friend Bernal, “‘Carnal,’ brother, your camera was your weapon” (25). The yellow light in Morey’s cartoon, moving impossibly through time and space, traces both the power and the trajectory of a weapon that can undermine the divisions that separate here from there and then from now. As Merla-Watson and Olguín affirm, “the speculative arts enable us to make…survivance into a visionary and potentially revolutionary force” (139). It is this force that is on display in Benitez Suite and is at the core of Borderlands 2.0’s speculative possibilities.