This article explores the idea of chemical borders that trap individuals in long-term medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD) in a prolonged period of liminality that progressively erodes their identity. It starts by contextualizing the US opioid epidemic. It then defines chemical border as physiological dependence on medications for OUD, such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. While useful in preventing relapse and accidental death from opioid overdoses, these medications can trap people in addiction treatment, creating a prolonged liminal space where identity erodes, and full recovery proves elusive. This state between active addiction and total abstinence delays full self-reconstruction and recovery. Chemical borders are invisible but powerful divisions between individuals and the sociocultural spheres that give their identities meaning. In this context, the article introduces the concept of eroded identity, a progressive loss of identity from chronic exposure to the stigma of addiction and prolonged MAT. The article focuses on Puerto Rican populations living in the continental US and highlights the tension between Hispanic cultural values and MAT programs. It concludes with a critical reflection on how these programs, by becoming a continuous and long-term medical regimen, lead to profound and sometimes irreversible changes in the self-perception of those suffering from an opioid use disorder, resulting in an erosion of identity.

Introduction: The Opioid Epidemic in the United States

To begin, it is worth highlighting the difference between opiates and opioids. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, these compounds have different origins and pharmacological structures. Opiates are natural compounds derived from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), which include morphine, codeine, and thebaine, while opioids can be natural, semi-synthetic, or fully synthetic compounds. Semi-synthetic opioids, manufactured by processing natural compounds, include heroin and the painkillers oxycodone (OxyContin R and Percocet R ), hydrocodone (Vicodin R ), and hydromorphone (Dilaudid R ). Finally, fully synthetic opioids like fentanyl and its analogs, methadone, and tramadol, are entirely synthetic and lack natural ingredients (Albores-Garcia and Cruz, 2023). Opioids also include prescription medications that treat acute chronic pain and illegal drugs like heroin. Opiates and opioids bind to opioid receptors (mu, delta, and kappa) in the central nervous system, releasing endorphins and dopamine and causing a strong sensation of euphoria and pain relief (Dhaliwal and Gupta, 2025).

In the United States, OUD has been established as a chronic, relapse-prone disease resulting from damage to the brain's reward neurocircuitry from continued opioid substance use (Heilig et al, 2021). Chronic illnesses have consequences beyond the health and well-being of those who suffer from them and their families. The opioid epidemic, for example, contributes to increased healthcare costs. As Holman (2020) has noted, the increase in chronic diseases is accompanied by a decrease in the quality of and access to health care. Similarly, Ansah and Chiu (2023) found that by 2050, the population aged 50 years and older in a multi-state population model will have at least one chronic disease. The authors suggest that policymakers explore the impact of interventions and prepare the necessary healthcare personnel to provide adequate care. The estimated cost of the third wave of the US opioid epidemic was $1 trillion in 2017 (Kuehn, 2021; Luo et al. 2021). This enormous sum includes increased criminal justice and health care costs, lost productivity, reduced quality of life, and premature deaths from opioid overdoses (Curtis et al., 2021). Treatment of OUD requires ongoing, long-term care (Stoicea et al., 2019).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines an outbreak as a rapid and unexpected increase in the number of cases of a given disease in a specific geographic area. An outbreak becomes an epidemic when the disease spreads to a larger number of people (CDC 2020). Although the term epidemic originally referred to the spread of acute infectious diseases, its current usage includes non-infectious, chronic diseases (Kalra et al., 2015). The government uses the word epidemic as a noun to indicate that the number of people using opioids is higher than their medical utility would indicate and as an adjective to denote their widespread use of these substances. According to the US Surgeon General (2019) the opioid crisis became an epidemic through a rapid escalation in the prescription and subsequent misuse of opioid pain relievers, and a consequent increase in opioid overdose deaths (Blanco et al,. 2020; Jalali et at., 2020; Stanford et al., 2021). For example, in 2010, physicians prescribed opioid medications at a rate of 81.2 prescriptions per 100 people (Lyden and Binswanger, 2019).

The over-prescription of opioids had other consequences, too. Visits to emergency departments due to misuse or abuse of Opioids Pain Relievers (OPRs) increased by 1.2 million in 2009, a 98.45% increase from 2004. Over the same period, admissions to substance abuse treatment programs increased six-fold, and the rate of overdose deaths involving OPRs surpassed that of illegal drugs like heroin and cocaine. Finally, the health-related costs to insurance companies due to the non-medical use of OPRs increased to 742.5 billion dollars annually (CDC, 2021). As a result, the government sought to decrease the use of OPRs after surgeries and hospital stays, imposed more rigorous controls on prescribing opioids, and implemented prescription monitoring programs (Jones et al., 2019). Although these new regulations had some effect, opioid overdose deaths continued to rise. Data from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) show an epidemic of prescription opioid overuse (Lyden and Binswanger, 2019). They also show that the rate of people using opioids increased from 17.8% of the population in 2015 to 20.8% in 2019 (Mattson et al., 2021). The NSDUH noted that nonprescription opioid use also expanded geographically, encompassing both urban and rural areas (CDC, 2021).

The CDC divides the opioid epidemic into three distinct waves. The first wave started by 1990, with the rise in prescriptions of semi-synthetic opioids (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone) for pain management (CDC, 2021). These OPRs, which had been reserved for treatment of post-surgical pain, severe injury, or terminal cancer, were being prescribed for chronic conditions like back pain and osteoarthritis. In 2011 a report from the CDC noted that drug overdoses involving prescription opioids tripled between 1991 and 2007. The second wave began in 2010, as government restrictions reduced the overprescription of OPRs and prompted a shift toward cheaper and more widely available alternatives, such as heroin (Cicero et al., 2014). The increased use of heroin caused a rise in overdose deaths. Three years later, the third wave had begun, with a movement away from heroin to the illegally manufactured fully synthetic opioid fentanyl (O’Donnell et al., 2017). In 1952, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)approved it as a pain reliever. Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine (DEA, 2024). There are also fentanyl analogues, which have similar effects to the original drug but are often fatal, are designed for street sale.

Data from the CDC (2023) show that from 2019 to 2022, drug overdose deaths continued to increase, reaching 107,941 in 2022. OPR-related deaths fluctuated, decreasing from 17,029 in 2017 to 14,716 in 2019, then increasing in 2020 to 16,416, and decreasing to 14,716 in 2022. Overdose deaths from illicitly manufactured fentanyl increased to 73,838 in 2022. Synthetic opioids (other than methadone) such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol are currently fueling the market for illicit substances, exacerbating the opioid epidemic (Tennyson et al., 2021) and causing the current number of opioid-related overdose deaths (Hedegaard et al. 2020). Between 2016 and 2017, 2.88 millions of 234 million (1.23%) adult visits to emergency departments in the US involved an opioid-related diagnosis such as opioid poisoning. Approximately 27.5% of these visits were due to opioid overdoses and represented a financial burden of $9.57 billion dollars. Medicare and Medicaid paid 66% of those costs (Douglas et al., 2019). In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic increased drug overdose mortality, especially in the Black, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native communities, widening existing disparities in the healthcare and criminal justice systems (Baroza et al. 2020; Friedman et al., 2024). These data indicate that fentanyl is driving the overdose epidemic, displacing deaths caused by OPRs. Currently, overdose deaths from fentanyl alone or mixed with cocaine or methamphetamine increased to 27,569 and 34,022, respectively, in 2022 (NIDA, 2021). Furthermore, the mixing of fentanyl with cocaine or amphetamines is possibly the fourth and current wave of the opioid epidemic. In response, the government is demanding greater access to methadone and other medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone to treat OUDs.

The high opioid consumption has global impact, as well. Richards et al. (2021), using data from the International Narcotics Control Board, found that between 2015 and 2017, approximately 700 tons of controlled opioids were consumed worldwide, averaging 32 mg/person per year. The US had the highest consumption, averaging 144 mg/person, followed by Oceania (132 mg/person), Europe (98 mg/person), Asia (3.5 mg/person), and Africa (1.4 mg/person). Robert et al. (2023) used VigiBase, the WHO's global database of Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs), to analyze the global use of the opioid analgesics oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine, tramadol, and codeine. The authors found that countries at the greatest risk for abuse of these opioids are Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the UK, and the US.

Opioid use also represents a challenge for Latin America. León et al. (2024) note that while average consumption is lower than in North America, Europe, and Asia, there is an alarming trend in some countries in the region. For example, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina reported a steady increase in opioid use over the past three decades, reaching a tenfold increase by 2023. Chile leads the way with an average of 1,692 daily doses for statistical purposes per million inhabitants (DDD), followed by Colombia (1,434 DDD), Argentina (1,050 DDD), Uruguay (840 DDD), and Costa Rica (502 DDD). This remains lower than that reported by the US (34,731 DDD). In countries with more limited access to opioid medications, consumption is much lower, as in Venezuela (27 DDD), Honduras (40 DDD), and Nicaragua (64 DDD). The authors call for attention to the lessons learned in North America, proposing stricter control and appropriate use of opioid prescriptions.

Opioid Use Disorder in Hispanic and Puerto Rican Communities

The Hispanic population in the US has witnessed a concerning rise in substance use disorders (SAMSHA, 2020). According to the 2020 NSDUH, approximately 12.7% of Hispanic or Latinx individuals aged 12 and older had a substance use disorder. Within this demographic, Puerto Ricans exhibit distinct vulnerabilities, with adults of Puerto Rican origin more likely to experience any mental illness (25.2%) or serious mental illness (7.1%) than other Hispanic subgroups. Because these elevated rates of mental health issues can complicate OUD treatment outcomes, the integration of cultural considerations into MAT programs is imperative.

Puerto Rico's colonial history and its ongoing political relationship with the United States have profoundly influenced Puerto Rican identity (Duany, 2002). The migration patterns between the island and the mainland have fostered a unique cultural duality. Within Puerto Rican culture, values such as familismo (emphasis on close family ties), respeto (respect), and dignidad (dignity) are paramount. However, prolonged participation in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) can conflict with these values. The structured nature of MMT programs, characterized by strict dosing schedules and regulatory oversight, may inadvertently isolate individuals from familial and social networks and leading to feelings of alienation and diminished self-worth. This phenomenon can lead to an “eroded identity” among Hispanics, and particularly among Puerto Ricans, who participate in MMT in the U.S. Factors affecting the commitment of Hispanics of Puerto Rican origin to recovery from OUD are

- Limited Access to Culturally Competent Care: There is a notable lack of MMT programs that address the specific needs of Puerto Rican individuals. This gap can lead to misunderstandings, mistrust, and reduced treatment adherence.

- Stigma and Discrimination: Negative perceptions of MMT within the community can discourage individuals from seeking or continuing treatment. The association of MMT with weakness or moral failure can exacerbate feelings of shame and isolation.

- Socioeconomic Challenges: High rates of poverty and unemployment among Puerto Rican populations can limit access to MMT and related support services. Financial constraints and lack of transportation can further impede consistent treatment.

- Language Barriers: Monolingual Spanish speakers face significant challenges in accessing and navigating MMT programs, leading to misunderstandings and decreased satisfaction with care.

- These issues require a multifaceted approach that integrates cultural competence into treatment programs, reduces stigma, and addresses systemic barriers to care. MAT that acknowledges and incorporates the unique cultural and historical contexts of Puerto Rican communities can more effectively support not only the physiological but also the psychosocial aspects of recovery, ultimately facilitating a more holistic and sustainable recovery process.

Chemical Boundaries

Forty-some years ago, Porter and Jick (1980) found that only two out of 946 hospitalized patients treated with an OPR developed an addiction to opioids, concluding that opioid medications were safe and seldom caused addiction in people without a previous history of addiction. By 2010, physicians were prescribing OPRs at a rate of 81.2 prescriptions per 100 individuals (Lyden and Binswanger, 2019). The wide availability and extensive use of opioid medications for pain control in the US occurred at a moment when pain was considered a fifth vital sign, along with blood pressure, temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate (Deweerdt 2019; Dowell et al., 2022; Lyden and Binswanger, 2019). The Sackler family, through Purdue Pharma and its best-selling synthetic opioid product, OxyContin®, took control of the development, marketing, and commercialization of synthetic opioid painkillers. Oxycodone, morphine, buprenorphine, and hydrocodone began to satisfy an avid consumer market for painkillers (Van Zee, 2009).

In 2016, the CDC reported more than 42,000 deaths from opioid overdoses. Based on that figure, in 2017 the Office of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared in a national public health emergency, which allowed it to address the opioid crisis, by, for example, allocating Medicaid resources to treat substance use disorders (SUDs). The government has renewed this declaration every year since. The opioid crisis has intensified, reaching 81,806 opioid-related deaths in 2022 and a decrease in life expectancy of 0.67 years in 2022 across all racial/ethnic groups (Hébert and Hill 2024). The opioid legacy reflects the Sackler family's extraordinary business success in marketing opioid painkillers and creating a new subjectivity: the opioid-addicted person. This subjectivity is also a revealing way to understand how ethnic and racial cultural values shape and are shaped by opioid-addicted people's ability to isolate, disconnect, and reconnect with worlds filled with meaning and explanatory narratives.

Throughout history, the use of certain psychoactive substances has generated imaginary communities of individuals, with boundaries that separate and unite people who share a common, albeit stigmatized, identity around the use of substances, which may or may not reflect unequal access to social resources and opportunities. The understanding of addictive behaviors has evolved from the violation of social norms to the current understanding as a chronic brain disease. Initially, the judicial system defined the boundaries of these communities, as those who used these substances were punished with long—but largely useless—terms of incarceration. Over time, the understanding of substance use as an individual pathology described by the terms "addiction" and "addict" prompted a transition from the legal system to the healthcare system. These terms and the emergence of medications to treat the condition, defined new borders of these communities. It remains controversial whether the population of the “addict” community suffers from a biologically defined disease based on alterations in the brain's reward system or a kind of developmental hijacking. To transfer addiction to a medical condition implies that addicts deserve medication-based treatment. The use of medications to treat the addict’s medical condition creates a chemical border that separates these individuals from their environment and themselves. These chemical borders also constitute tacit frameworks that regulate these subjects' social interactions, thus producing an objectified form of difference. One consequence of this objectification is stigmatization.

Research show that even small changes in the language of addiction have a large influence on the self-concept of people with SUD, their families, professional service providers, and the community at large (Ashford, 2019). More sensitive language could change the way people affected by SUD and their providers think of and behave around treatment, contributing to a change in the view of those affected as weak or complicit and therefore deserving of punishment. The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) included some changes in its terminology, replacing the terms dependence and abuse with substance-related and addictive disorders (Pivovarova and Stein 2019). This change is intended to prevent pejorative labeling of people dealing with SUD (e.g., addicts or drug addicts), decrease stigmatization (Stangl et al., 2019), and reduce inequalities in access to treatment services (Kelly et al. 2016). The updated version of the fifth edition of the DSM, released in 2022 as DSM-5-TR, retained this language.

Similarly in 2013 the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recommended the use of clinically driven, unified language for addiction and substance-related disorders to protect access to treatment. ASAM, which focuses on developing criteria to assist clinicians in placing people at an appropriate level of care, recognizes that diagnostic decisions require both objective criteria and clinicians’ subjective interpretation. More sensitive language could change the way people affected by SUD and their providers think and behave about diagnostic decisions and treatment. To that end, ASAM proposed specific language to refer to SUD, including the words individual, person, participant, and patient. ASAM assumes that these words imply a holistic biopsychosocial view that is lost with terms like clients, customers, or consumers. Also, ASAM uses the term opioid treatment services to refer to the use of medications (not limited to opioid agonists) with or without associated psychosocial services. In other words, ASAM's proposal formalizes the chemical boundaries that separate addicts from the cultural environment where they develop and sustain their addiction.

Despite the efficacy of three FDA-approved medications for the treatment of OUD—methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone (Azhar et al. 2020; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019)—stigma has led to their underutilization (Witte et al. 2021). Cheetham et al. (2022) identified the impact of stigma among people with OUD at three levels: structural, public, and internalized. The first involves the unfair allocation of resources for the treatment of OUD compared to other medical conditions. The second, the public level, concerns organizational norms that govern the relationship between treatment providers and people with OUD, leading to a stereotypical view of these individuals as lacking motivation to achieve long-term recovery and not deserving of treatment. Finally, internalized stigma is the result of structural and public levels of stigma that reinforce the notion that people with SUD have a disempowered identity and lower level of achievement. In this sense, addiction, as conceptualized and promoted by Volkow (2019), Heiling (2021), among others, emphasizes the chronic and relapsing nature of addiction. This conceptualization and its consequences provide the basis for eroded identity. In fact, repeated failures (relapses, social rejection) can erode a person's core identity and hinder recovery.

To mitigate the impact of stigma, the government has called for a change in the language used to describe addiction. The Executive Office of the President, through the Drug Enforcement Administration's Office of Drug Control, issued a memorandum urging executive branch agencies to modify this language. The document, which is a guide rather than federal regulation, addressed the terminology used to refer to substance use and SUDs. Based on the DSM-5, the most important change is to use language that is neutral rather than pejorative (e.g., person with a SUD instead of addict). While valuable, this suggested shift in the language of addiction creates a gap where pathology and medications for treating SUDs draw a thin, almost imperceptible line that underscores the chemical border.

The chemical border imposed by MMT creates a prolonged period of instability in the identity of the person in recovery. These medications create a liminal state (Turner 1969) where stigmatized, pathologized, medicalized, and pharmacologically controlled individuals delay their transition to a fully recovered identity. Although chemical borders are strong, they generate fragility in these individuals. As an example, consider policy regulations that prevent the person in recovery from accessing medication. The unilateral decision to discontinue medication, particularly methadone, at a harmful rate of reduction, causes withdrawal symptoms that the person in recovery describes as worse than those produced by discontinuing any other opioid. Instead of embracing a reconstructed identity by resuming roles that were neglected due to drug use, the chemical border produces a prolonged and ambiguous transition, an intermediate state in which individuals are neither drug users nor recovered, leading to a progressive erosion of the recovering person's identity. The chemical boundary produces a new subjectivity, one that we can call eroded identity.

Liminal Subjects

According to anthropologist Victor Turner (1969), liminality and prolonged transition refers to the ambiguous, in-between state that people experience during rites of passage. Turner builds upon Arnold van Gennep’s three-phase model of rites of passage—separation, liminality, and incorporation—but he emphasizes the liminal phase, when individuals are between their past and future social roles. This stage is characterized by disorientation, ambiguity, and the dissolution of previous structures, leaving participants in a fluid, threshold state. In prolonged transition, individuals or groups remain in the liminal phase for an extended period without reintegration into a stable social structure. This prolonged liminality can create uncertainty, social alienation, and identity destabilization. The longer the liminal phase, the greater the risk of personal or social fragmentation. Liminality and prolonged transition, as theorized by Turner, provide a framework for the eroded identity that results from an indefinite threshold state. When the transition to a stable identity is impeded, the self gradually fragments, leading to existential uncertainty, alienation, and disorientation.

How Liminality and Prolonged Transition Contribute to Eroded Identity

- Loss of Social Anchors: When individuals or groups remain in a prolonged liminal state (e.g., methadone maintenance treatment), their sense of self erodes in the absences of stable cultural, social, or institutional anchors.

- Chronic Uncertainty: Unlike temporary rites of passage that have a clear endpoint, prolonged liminality offers no resolution, leading to a fluid and unstable identity.

- Disintegration of Role and Meaning: If individuals are unable to reclaim a social role or establish a new one, their self-perception deteriorates. For example, in postmodern societies with unstable careers, shifting relationships, and rapid technological change, people may struggle to define themselves.

- Alienation and Marginalization: Those stuck in prolonged liminality may be seen as outsiders or socially invisible, which further weakens their identity.

Eroded Identity

The opioid epidemic in the US is a public health and economic crisis, but it is also a profound social transformation in which identities are remade, contested, and ultimately eroded. The notion of eroded identity provides a framework for understanding how clinical regimens such as methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and other medications used to treat OUDs impose a label. Labeling individuals as “addicts in MMT” or “Persons In Recovery under medication treatment” transforms both their subjectivity (the way they experience themselves) and their intersubjectivity (the way their identities are recognized and negotiated in social interactions).

Inclusion of the word “identity” in the concept of eroded identity is neither casual nor rhetorical, but rather a critical theoretical decision. To use the word “identity” in the context of prolonged exposure to medical interventions that create a chemical border around people seeking help to recover from their OUD reflects an epistemological and ontological commitment: identity is a non-pathologizable, non-medicalizable, and non-pharmacologicable construct. Unlike clinical descriptors such as "symptom," "disorder," or "deficit," "identity" resists medical abstraction. Symptoms are observable phenomena tied to underlying conditions. Disorders are deviations from statistically or biologically defined norms. Deficits imply measurable loss or dysfunction. In contrast, identity is not quantifiable, cannot be imaged through diagnostic tools, and has no normative endpoint. For example, while a clinician may diagnose anhedonia as a symptom of depression, there is no clinical diagnosis of fragmented identity. Similarly, addiction may be treated as a disorder, but a loss of sense of self, purpose, or narrative coherence—the hallmarks of eroded identity—do not fit DSM categories. This distinction is vital because it marks the frontier where medicine ends and lived experience begins.

The medicalization of human experience often begins by pathologizing deviation from norms. Depression becomes a serotonin imbalance, anxiety a dysfunction of the amygdala, and addiction a brain disease. While addiction is considered a brain disease, identity is not a deficit, disorder, or dysfunction. A lived, constructed, and evolving process, identity is not a deviation from a normative foundation. Because identity is not pathologizable, the experience of being disconnected, in flux, or liminal is not a symptom, but a condition of being human, and eroded identity a social and existential outcome. To pathologize identity is to fundamentally misunderstand its fluid and dialogical nature. Rather than a static entity that can be fractured, identity is a process of becoming, a negotiation between self and society, memory and imagination, the internal and the external (Hall 1996; Ricoeur 1992).

When individuals undergoing long-term MAT are evaluated within a pathological framework, their identity becomes over-coded with clinical descriptors like “noncompliant,” “chronic,” or “incomplete.” These terms cannot capture the existential weight of living with a suspended, ambiguous, or fractured identity as a result, the prolonged liminality of extended exposure to medical interventions—for example, MMT for OUD—can erode identity.

Identity is also not medicalizable. Medicalization, as Peter Conrad (2007) defines it, is the process by which non-medical problems become defined and treated as medical ones. Addiction has undergone this transformation: once a moral failure, it is now treated as a chronic disease. While this reframing reduces stigma in some ways, it creates new forms of biopolitical control that turn patients into long-term subjects of medical regimes (Foucault, 1979; Rose, 2007) subject to the chemical borders of OUD medication. Identity resists this capture. While the medical system may attempt to categorize the subject's physiology, identity rejects such categorization. Identity is not constituted by diagnosis, but by narration, meaning making, and relationality. The experience of someone on long-term methadone maintenance treatment, for instance, cannot be fully captured through dosing schedules, toxicology screens, or treatment plans. In addition to dependency, they struggle with recognition, purpose, and self-understanding—dimensions that lie beyond the reach of medicine. To declare identity non-medicalizable is to decenter the clinic as the sole arbiter of legitimacy and healing and to assert that identity cannot be confined to progress notes, lab results, or diagnostic criteria. Medicine cannot resolve the existential dilemma of who someone is or who they are becoming.

Finally, the assumption that pharmacological intervention can lead to “recovery” relies on an implicit teleology of return, an idea that individuals will regain a prior, stable, pre-addiction identity. But many individuals, especially those with histories of trauma, marginalization, or long-term drug use, have no such identity to return to. These individuals must construct a new identity, and no medication can facilitate that process. There is no drug for narrative reconstruction, social reintegration, or existential coherence. Medication may sustain life, but it does not provide meaning. The longer individuals rely on pharmacotherapy without being offered meaningful avenues for social, relational, or vocational reintegration, the more likely they are to remain suspended and trapped in a liminal (Turner, 1969) or twilight zone where the self is neither totally lost nor totally recovered. I call this state eroded identity. In the context of OUD, pharmacological solutions like methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone can reduce harm, prevent relapse, and stabilize lives, but they cannot restore identity or rebuild selfhood.

Eroded identity is a new concept to describe how prolonged exposure to stigma, especially in pharmacological treatment for addiction, leads to a deep and often irreversible transformation of self-perception and social positioning. Eroded identity refers to the gradual deterioration of one's sense of identity due to prolonged internalization of stigma and social exclusion. In fact, repeated failures of addiction, like relapses and social rejection, can erode a person's core identity and hinder recovery. Unlike stigma, which can be resisted or managed, eroded identity amounts to a deep-seated loss of personal agency that makes self-reconstruction difficult. Eroded identity differs from "spoiled identity," a term coined by sociologist Ervin Goffman (1963). Spoiled identity explains how people with socially devalued attributes manage their identities. For example, a deeply discrediting attribute such as addiction makes the individual different in social interactions. Labeling individuals as “addicts” transforms their subjectivity (the way they experience themselves) and their intersubjectivity (the way these identities are recognized and negotiated in social interactions), and these individuals may attempt to pass as non-addicted or adopt a countercultural identity. In contrast, eroded identity results from life under clinical supervision without social recognition, pharmacologically stabilization but existential suspension, and being defined from the outside (as “addict,” “patient,” “person in recovery,” or “noncompliant”) with no viable way to re-author one’s own story. In this framing, eroded identity is not a side effect of MMT, but rather the cost of reducing identity to something medicine can control. It reflects the limits of the medical gaze, and calls for a broader, more humane understanding of recovery as a social and narrative process, not merely a clinical outcome.

Table 1: Comparing Stigma and Eroded Identity

|

|

Stigma |

Eroded Identity |

|

Definition |

Stigma is a mark of social disgrace that discredits a person’s identity. |

Eroded identity is the gradual breakdown of the sense of self due to prolonged internalization of stigma and social exclusion. |

|

Identity Management |

Individuals manage stigma by “passing” (hiding the stigma) or “covering” (minimizing its impact). |

Individuals lose the ability to construct a stable sense of self and experiencing identity fragmentation. |

|

Agency and Adaptation |

Individuals may resist, redefine, or accept their stigmatized status. |

Individuals engage in learned helplessness, making self-reconstruction more difficult. |

|

Reversibility |

Stigma can be managed, reduced, or challenged through social acceptance or personal resilience. |

Eroded identity entails a deeper loss; individuals struggle to reclaim a coherent sense of self even after external stigma is reduced. |

|

Application to Addiction |

Addicts may try to "pass" as non-addicts or embrace a counterculture identity. |

Long-term stigma and repeated failures (relapse, social rejection) can erode an addict’s identity and make recovery difficult. |

Core Components of Eroded Identity

- Chronic stigma and internalization: Long-term exposure to social stigma (e.g., “once an addict, always an addict”) results in the internalization of negative labels (self-stigma) that reinforce behaviors that sustain addiction. Individuals transition from feeling stigmatized to fully identifying with the stigmatized label.

- Identity Disintegration: The self is progressively shaped by addiction, leading to a loss of former identities (e.g., family roles, professional identity). Narratives of failure and hopelessness dominate self-perception.

- Social Alienation and Loss of Meaning: Repeated cycles of addiction and recovery attempts lead to disconnection from social networks. The loss of social roles contributes to a lack of purpose beyond substance use.

- Learned Helplessness and Reduced Agency: As identity erodes, individuals struggle to see themselves as capable of change.

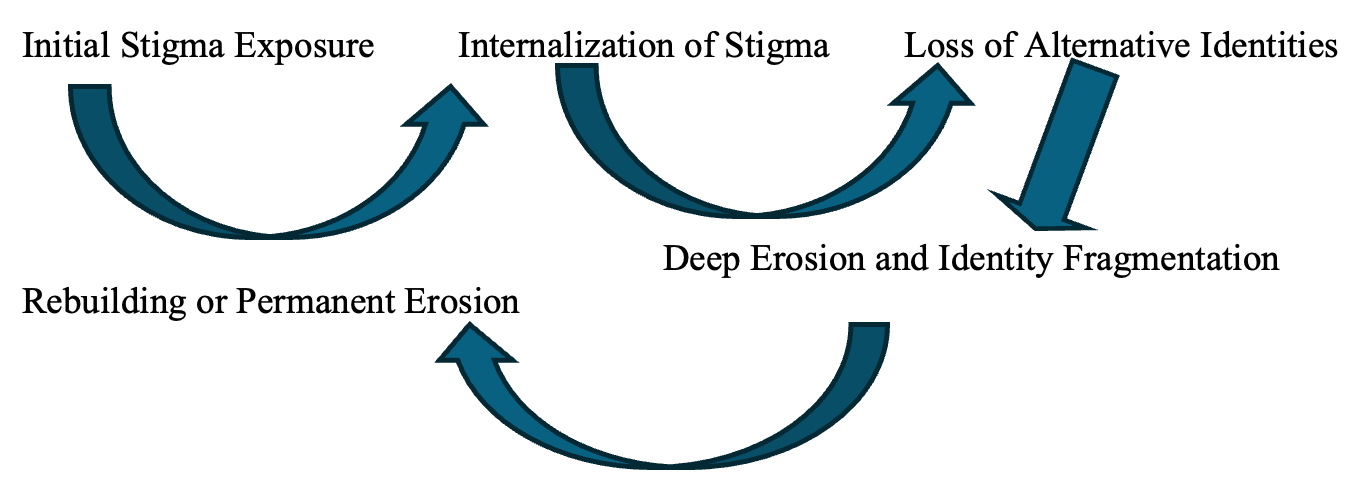

Figure 1. Stages of Identity Erosion in Addiction

The Impact of Prolonged Medication-Assisted Treatment on Puerto Rican Communities

As noted above, chemical boundaries refer to physiological reliance on MMT medications that impose a perceived barrier between individuals and their pre-addiction identities. While MMT provides physiological stabilization, it may not address the underlying psychosocial and cultural factors essential for holistic recovery. For Puerto Rican individuals, this absence can impede the reclaiming of cultural identity, especially when societal stigma associates MMT with ongoing addiction rather than recovery.

For Puerto Ricans in long-term MMT, identity erosion stems from the prolonged medicalization of recovery. Puerto Rican identity is uniquely shaped by a colonial relationship with the US that keeps the island in a liminal political space—neither sovereign nation nor fully integrated state (Briggs, 202). This mirrors the space that individuals in long-term MMT occupy: a suspended state of "not quite sick, but not quite well" (Turner 1969). Inhabitants of this medical liminality face compounded experiences of surveillance, dependency, and ambiguous belonging that characterize both OUD treatment and Puerto Rican sociopolitical life. Furthermore, as clinical regimes prioritize compliance and biochemical metrics, the relational, cultural, and existential dimensions of selfhood are marginalized. The same structures designed to support recovery—fixed dosing schedules, clinical surveillance, and pharmacological dependency—can reinforce cultural alienation and narrative fragmentation. This erosion is exacerbated by historical and cultural factors. Puerto Rican identity is shaped by the colonial legacy, transnational movement, spiritual traditions, and collective memory (Briggs, . Treatment frameworks that ignore these elements contribute to the slow unraveling of the self as recognized by one’s community. The result, a chemically stabilized body and socially estranged identity, is a condition that medicine alone cannot remedy.

Methadone programs in Puerto Rico also operate under a carceral logic of compliance and control. According to Hansen (2018), the structure of many clinics in San Juan mimic punitive institutions, where patients must adhere to rigid dosing schedules, often under surveillance, while facing stigma from both health professionals and the broader society. Also, migration between Puerto Rico and the US mainland can disrupt continuity of care and community support. A person receiving MAT in Puerto Rico may face a disruption in their treatment if they move to New York or Florida, for example, interrupting medical stabilization as well as symbolic and emotional ties.

In addition, MMT programs in the mainland US are not always equipped to meet the cultural and language needs of Puerto Ricans. Many programs are designed around mainstream, individualistic models of recovery that emphasize personal responsibility and self-management, values that may conflict with Puerto Rican ideals of familismo, collective identity, and spirituality (Varas-Díaz et al. 2010). This cultural mismatch contributes to an erosion of self-perception and belonging, as individuals are alienated from both clinical and community settings.

The chemical boundary of MMT is also structural. Daily dosing requirements make it nearly impossible to engage in spontaneous cultural rituals or long-distance family gatherings. A patient bound to a methadone clinic cannot easily travel for a funeral in Puerto Rico, for example. The forced absence from culturally meaningful events slowly erodes one's ability to participate in the cultural practices that affirm identity. The impact is particularly significant among Puerto Rican men, for whom masculinity is often linked to autonomy, familial responsibility, and dignity. Prolonged MMT can replace these roles with an image of medical dependency. The individual becomes re-inscribed in the same logics of control and dependency that Puerto Rican people, as a colonized population, have historically resisted.

Conclusions.

In the context of the US opioid epidemic, and the prolonged use of MMT, eroded identity provides a powerful lens for understanding the formation of addicts’ identities. By holding that identity is non-pathologizable, non-medicalizable, and non-pharmacologicable, the concept of eroded identity emerge not as a clinical failure, but as a social and existential consequence of prolonged liminality under institutional regimes that attempt to stabilize identity through medical control.

While MAT plays a critical role in the management of OUD, its prolonged use can inadvertently contribute to the erosion of identity, particularly among Puerto Rican individuals whose cultural values and historical experiences shape their recovery trajectories. Addressing this issue requires a multifaceted approach that integrates cultural competence into treatment programs, reducing stigma, and addresses systemic barriers to care. By acknowledging and incorporating the unique cultural and historical contexts of Puerto Rican communities, MMT can more effectively support not only the physiological but also the psychosocial aspects of recovery, ultimately facilitating a more holistic and sustainable recovery process.

Eroded identity is a call to break chemical boundaries, to go beyond pathology, medicalization, and medication to understand that recovery entails dimensions related to self-discovery and that it is rooted in racial and ethnic cultural values, identities, and connections to the environment where recovery takes place (Guzman, 2024). Recovery also represents a crisis of internalization of the cultural category of addict, as reflected in the term "recovered addict." Treatment must be reimagined beyond biomedical stabilization to rebuild identity through recognition, belonging, and the restoration of meaningful social roles. Culturally responsive and flexible MAT would include mobile dosing units, culturally embedded peer support, and narrative therapy rooted in Puerto Rican history and cultural expression.

Most recovery research is conducted within the context of mainstream American culture and it does not reflect the experiences of minority groups. For example, the mainstream American cultural values of personal responsibility, individualistic understanding of health, and freedom of choice (Hook and Rose, 2020) favor individual accountability for initiating and maintaining recovery. This contrasts with collectivist cultures (Krys et al., 2021), such as Hispanic cultures, which emphasize and value close social and familial support (Gast et al., 2017; Guzman 2024). Research also shows that Hispanics have lower treatment completion rates and longer treatment duration than non-Hispanic whites and African Americans (Alvarez et al., 2007; Mennis et al., 2019). These disparities in SUD recovery are prevalent across all ages and affect psychotherapy outcomes . For example, Hispanic men can rebuild a sense of identity through a progressive reconnection with their ethnic cultural values, a deeper process that implies profound transformation rather than a linear process of change (Guzman, 2024).

The concept of eroded identity invites a fundamental rethinking of how we understand the self in the context of medical treatment. Unlike disease, identity cannot be diagnosed, prescribed, or cured. It is not a malfunction to be corrected but a lived, storied, and relational phenomenon that must be socially recognized and culturally situated. MAT offers critical physiological stabilization, but it cannot reconstruct the narrative or cultural coherence that sustains identity.

To fully meet the needs of individuals in MMT, we must move beyond the clinical gaze and embrace interdisciplinary, culturally responsive approaches that recognize identity as an emergent and communal process. Social reintegration, narrative reconstruction, and cultural re-embedding must be treated as essential components of recovery. Only then can we begin to repair what pharmacology cannot: the fragile, dynamic, and profoundly human phenomenon we call identity.