1. A recent history of erasure

If the border is a border then it’s many borders plaited sobre sí. Le dicen herida abierta pero es un delta que se inunda, fértil y vivo, contra el concreto. (Anzaldúa, 1987) Es el encuentro de múltiples programas de modernidad, pero también de aspiraciones y deseos individuales, de privilegios y carencias, y de estrategias, visibles e invisibles, de control poblacional. Importantly, it is at borders where aesthetic genealogies often meet, migrating with humans, who carry their know-hows on beauty in life with them everywhere they go.

In their versatility, borders are often conferred the arduous privilege of opening spaces of opportunity to different social stakeholders. On the one hand, está el migrante, que atraviesa la frontera buscando mejor vida. Por otro lado, however, está el opportunism de las regional elites, who conceive of the border space as a jumping off platform towards spaces of global relevance. This classed distinction frames all borders, as they are simultaneously buttressed as loci of international fluidity and of exclusionary state control. Such logic is not alien to the cultural field, where plentiful organizations have cheered borders, The Border, for its cultural differential value, while relying on—and, as a result of their work, often occluding—material conditions of demographic exclusion and economic exploitation.

One such example was inSITE, a festival of site-specific art that took place in San Diego and Tijuana (1992-2005). Inaugurated as a direct response to the signature of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) this exhibition of contemporary art sought to display to international art publics the richness of this region, hoping to counter its established reputation as a land of violence. At its program’s core was a deep belief in the seamlessness of the borderlands, as well as in art’s capacity to highlight, and blend into, the border’s supuesta porosidad. This border-spanning art biennial promoted ideals of convergence and unity through artworks commissioned for spaces within and beyond the gallery. In the catalog for the 1994 iteration, Mexican curator Cuauhtémoc Medina wrote

Íbamos y veníamos como espectadores artísticos: seres adheridos al tiempo y abstraídos de la realidad inmediata. Íbamos de ahí para allá para ver las piezas de una exposición y tratar de articularla entre todos en la cabeza, y para interpretar la línea divisoria entre México y los Estados Unidos como objeto poético y vertedero de historia. Se me concederá que esa transgresión de los usos de y lectura corrientes de los objetos es lo mínimo que hemos de esperar de un género como el de la instalación, de la que podría sostenerse que es la reiterada comprobación de que el ser de las cosas es un resultado de sus condiciones de observación y aparición, y no algo eternamente convenido y establecido en todo lugar y en todo el tiempo, o de los proyectos in situ, que hace aparecer los signos de un lugar que la mirada corriente cree invisibles, callados o improbables (Medina 1994).

And this was the seamlessness that the art festival cheered. Started by local elites with, indeed, a seamless experience of borderland life, inSITE reflected their smooth transborder mobility. It would not be the first or last cultural organization to misrepresent the complex negotiations that the majority of the regional population experience on a daily basis.

In large part commissioned by the organizers to foreign artists with little knowledge of place, most artworks in inSITE represented San Diego and Tijuana through formal languages at the time trending in the global art capitals. This selection criteria reflected the organization's desire to turn the San Diego-Tijuana region into a new exciting destination for global contemporary art tourists—a desire not infrequent during the globalization that followed the end of the Cold War. For example, Mexico City-based Sofía Táboas’s installation, Doble Take / Doble turno (1997), blocked a hallway in la Casa de la Cultura de Tijuana con un large cubo that rehearsed Minimalism’s formalist occupation of the gallery space—despite its use of plastic beads instead of rougher materials directly associated with this movement, such as concrete or plywood. Although British artist Andy Goldsworthy sourced clay from a local canyon for his sculpture Two Stones / Dos piedras (1994), his emphasis on materiality at the expense of other dimensions reduced his engagement with the borderlands to a transportable formalism. Each of these examples succeeded in addressing this region in terms that were legible to a nascent global elite familiar with the late 20th Century inheritances of North Atlantic art genealogies.

Elsewhere, I have referred to these and similar processes as instances of aesthetic conversion, by which realities previously off-limits to the category of art are inscribed as such through their reframing via established aesthetic paradigms, provoking not only superficial alterations in them but, chiefly, ontological transformations with important socio cultural repercussions (Checa-Gismero 2024). De este modo, la frontera, through these artworks, became art, al ser enunciada en los mismos términos que otros escenarios of global relevance, becoming more visible, and thus accessible, to participants in the global contemporary art world. Importantly, though, through these aesthetic conversions, the border itself would be looked at with the reverence that audiences confer to artworks—albeit in a pacified manner.

Part of a longer history of erasing violence in land through aesthetic conversions, la frontera se volvió bella. Y al volverse bella se pacificó... at least in appearance. As with other fronteras in colonial histories, ongoing violence—by the state and by individuals—did not make it into the period’s canonical accounts. Nowhere in the artworks are the vigilantes policing the area, nor the harassing Border Patrol, the exploitative labor practices for Mexicans in San Diego, or the incendiary, anti-migrant speech of elected officials. In big part as a result of the several inSITE exhibitions, the term ‘Border Art’ became associated in the global art world imaginary and its accompanying literature with poetic approaches to the beauty of migration and global seamless mobility—with good examples in the work of inSITE artists Francis Alÿs and Alfredo Jaar.

Against this superficial engagement with the borderlands I propose to privilege artworks formulated from the “borderlands condition” (Checa-Gismero 2024). Esta condición está marcada por la dialéctica entre, por un lado, procesos disciplinarios institucionales (que afectan a los cuerpos, la cultura y el tiempo de los sujetos) y, por otro, la vida cotidiana de los sujetos en la región, cuya naturaleza situada les garantiza un conocimiento de primera mano de la zona. Presente en un grupo reducido de obras expuestas en inSITE, like Tonguetied / Lenguatrabada (Border Art Workshop / Taller de Arte Fronterizo, 1997), este enfoque ya marcaba una larga tradición de producción artística en la frontera, chiefly aligned with the emancipatory programs of Chicanx Civil Rights activism and its most recent inheritances.

2. La frontera hoy: COGNATE and the borderlands condition

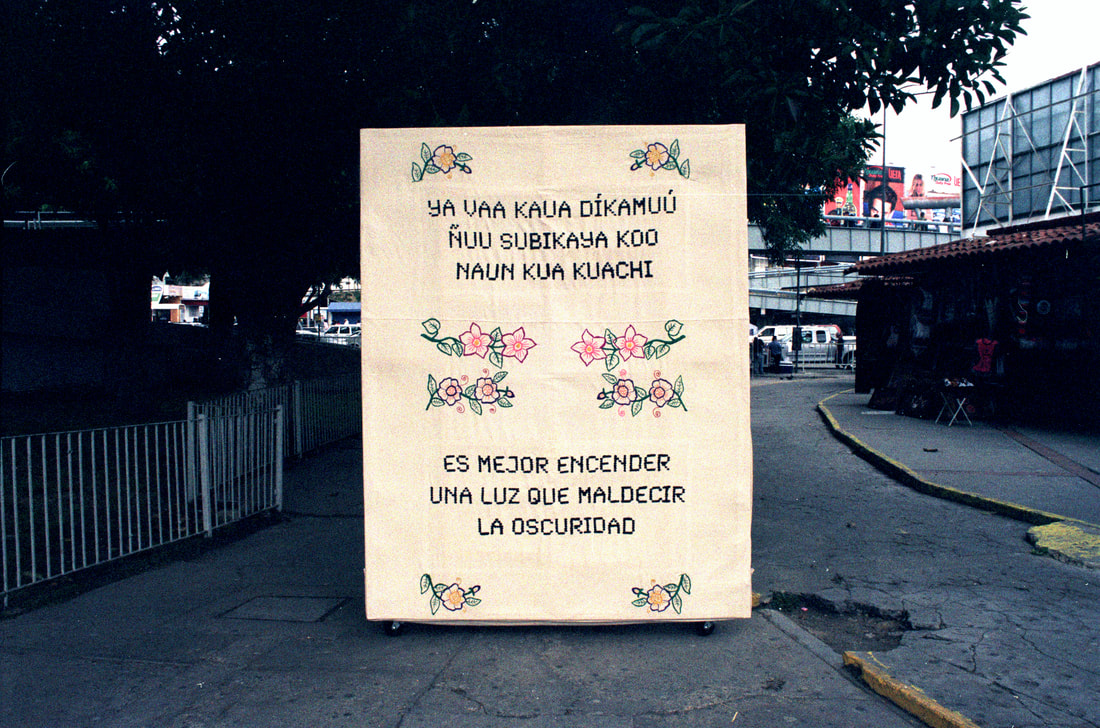

Ya vaa kaua díkamuú ñuu subikaya koo noun kua kuachi.

Es mejor encender una luz que maldecir la oscuridad.

reads a large scale canvas embroidered in Mixteco and Spanish. Cuatro flores enmarcan las frases, four others grow in-between. Stretched on a mobile platform, the large canvas está de camino al San Ysidro port of entry, on the Mexican side of the US-Mexico border’s west end. Its makers are Mujeres Mixtecas, a collective of Indigenous women from the Mexican state of Guerrero living in Tijuana, where they work selling chocolates and crafts to the cars waiting to cross la línea. Caminan entre los vehículos vendiendo their goods to bored cross-border commuters. Often, their kids accompany them—running around, saddled on their backs.

The canvas registers an attitude to artistic work that permeates through the practice of San Diego-Tijuana artist collective COGNATE. Since 2011 Amy Sánchez Arteaga y Misael Díaz have worked to document and intervene in the forms of life and work that are endemic of the US/México frontera, con especial atención a las oportunidades para resistir y crear that emerge out of the encounter of different cultural, economic, and legal frameworks. As the canvas shows, theirs is a practice anchored in collaboration that centers labor, materials, and language as the loci of intercultural exchange. Theirs is a work that speaks of the borderlands condition from its lived experience. Muy importante es el esfuerzo que COGNATE ponen en documentar y legitimar the forms of life and culture that emerge from and around the experience of migration.

Es mejor encender una luz que maldecir la oscuridad. COGNATE & Mujeres Mixtecas, 2012

COGNATE are a binational collective of socially engaged artists who work in the western-most end of the US-Mexico borderlands. Originally from the region, the San Diego/Tijuana based duo work to represent and intervene in the complex social fabric of the borderlands, with a commitment to amplifying the lives and cultural practices of those involved in the experience of migration. The embroidered canvas is a result of months of work between them and Mujeres Mixtecas. It all started in 2012 when, in residency at a storefront within the local craft market, the artists organized open language exchanges in Mixteco, Spanish, and English. Drawing a plane field for the three, the dialogical spaces fostered by the artists attracted diverse members of the regional community: members of the Tijuana art scene, market store owners, tourists wandering around the market, and itinerant vendors like the women behind the bilingual canvas.

These spaces for dialogical encounter honored the collective’s name: cognates, o cognados, son palabras en idiomas diferentes that share meaning and etymological root. In these exchanges the artists learned about the constant harassment that the itinerant vendors women were subject to. The women didn’t have permits, and the local police chased them around, often seizing their goods and at times taking their kids to the local orphanage. But it so happened that market stores were in themselves already permitted, and so COGNATE invited them to work within their space, shielding their bodies and work with the permit attached to the artists’ residence space. This partnership allowed the women more than protection from the local police. For the next few months they were able to set up a sewing shop and work on commissions, such as school uniforms, as well as on textile artesanías, securing a higher and more stable income than their previous work at the port of entry.

Ni autónomo ni heterónomo, art, as practiced in North Atlantic modernity, can open spaces of temporary autonomy—even as it functions in heteronomy with social life. Like the bracketed space that COGNATE opened in their studio, these temporary states of autonomy can provide room for resistance within state violence from where to practice life otherwise—as long as they are formulated from the deep knowledge of site that only situated practice can offer. Así, practicando desde la borderlands condition, COGNATE’s projects have the capacity to change the world, in the here and the now. Durante el tiempo que la shop estuvo abierta, las Mujeres Mixtecas were not harassed by the police and had a safe environment to sew and earn a living. Even if only temporarily, practices like this one set a factual precedent for everyday praxis as dialogical and decentered, working as templates necessarily situated within the specific conditions at place within particular historical conjunctions.

It seems that one of the things that socially engaged art can do, or perhaps one of the ways it can participate in broader efforts to both represent and resist escalating violence en la frontera, is to both shelter and practice otherwise, to amplify and invite appreciation of the often invisible social labor practiced by those who, in addition, also practice the very visible, material work that feeds us, cares for us, drives us, and builds our homes. I can think of other now canonical examples of socially engaged art that are anchored in aesthetic conversions that attribute cultural worthiness to other forms of invisible labor (feminist art practices, for example) and have successfully reformed established canons to reassert the value of worldviews and bodies formerly excluded from them.

3. ¿Y ahora qué?

En este breve ensayo retraté la frontera como un portal liminal for the ongoing aesthetic conversions that enrich dominant artistic repertoires from the so-called margins of cultural production. As we try, once and again, to portray the many borders that inform this complex space, one might be careful not to forget the implications these seemingly innocuous conversions can have in the material world. What is erased, and then upheld, with each of our discursive moves? ¿A qué paradigmas de valor estético recurrimos como medida de cambio? Whose lives are signaled as mattering via these aesthetic conversions? May these questions, that arise from the lived experience of the border, guide us through our analytic and didactic practices all over, as the forms of slow and fast violence rehearsed at The Border, spread all around us.