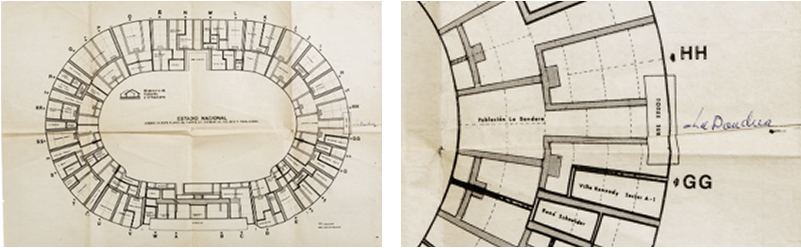

A 1979 folder with a crumbled sheet of mimeograph paper, marked by staples and containing a diagram, was the last trace of an event that had disappeared from the official history of a country (Fig 1 and 2). The finding unfolds a larger story hidden around the corners of sixty shantytowns of Santiago’s margins. The scheme had been used to organize 37,000 residents of Santiago’s outskirts during a mass event at the National Stadium. While much has been written about Chile’s National Stadium as a detention camp during the dictatorship, little attention has been paid to its later use as a space of bureaucratic control over marginalized populations. In the fields of documentary studies and urban history, the role of architecture as a site of both memory and control is widely debated, especially regarding spaces like the stadium, a symbol of both sports and state violence. This gap might be addressed by examining a unique archival document (Figure 1-2). A drawing that had been prepared for a bureaucratic event, which processed land titles, transforming squatters into both property owners and debtors. Preserved by one the residents for over 40 years, the document sheds light on the stadium’s role in shaping the city’s invisible margins.

By scrutinizing this drawing alongside press clippings, audiovisual material, and oral testimonies, we see how the stadium, once a site of imprisonment, became a device for controlling the city’s population. The tensions between fiction and reality in these archival materials highlight the political and social forces at play in transforming urban space. As the folded sheet's story unravels, a three-fold enterprise emerged: a scientific, political and literary narrative, as framed by Ranciere[1] in the Names of History. This is a story that is scientific, in the sense of systematic searches of veiled phenomena; that is political as much as anonymous subjects and communities are confirmed or denied ‘by an appeal to history’; and that is literary regarding techniques of writing and presenting history: the question of words in relation to things, the names and events of the past, and the invisible order and forces behind them. Ultimately, the drawing reveals how a seemingly neutral monument functions as a tool for geopolitical control, making visible the hidden dynamics of urban governance in Santiago.

Figure 1 and 2: sheet of mimeograph paper with a stadium plan that circulated in a booklet published by Ministry of Housing and Urbanism. 29th of September 1979. Source: La Pancha, resident of La Bandera shantytown. Also found at Biblioteca Nacional de Chile.

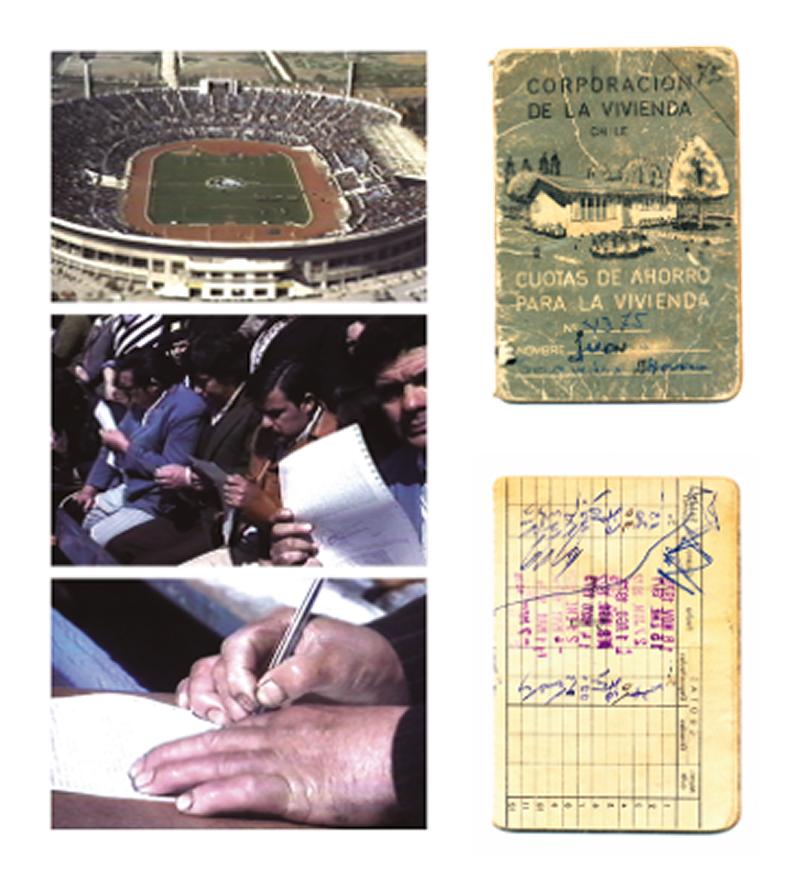

“Their hands forced by uncertainty, on the morning of Saturday, September 29, 1979, the pobladores descend en masse upon the National Stadium; they arrive with doubts or fears or with unjustified confidence, but they arrive. The doors open at eight thirty and close an hour later. Aided by over 2,000 functionaries of the Housing Ministry, the crowd settles into the places reserved for them on the diagram. An aerial shot shows the Stadium’s stands semi-full; the unquestioned official figure of 37,000 pobladores seems realistic. There are clear groups, islands of an archipelago: the crowd organized in a way that, if they were soccer fans, would seem artificial.”[2]

The drawing was found in awalk through shantytowns in the margins of Santiago, one of many walks made by the research team between 2016 and 2018. One of the settlers, la Pancha, showed up with an intriguing scheme in her hands. The sheet of paper was ekphrastic: a plan describing an event that superimposed a cartographic and a narrative impulse in the same vivid gesture. This was not a conventional archival finding made in a library, a deposit, or an archive, but one that came from the street in a rather ethnographical mode. The mimeograph paper with staples in the fold suggested that it had been part of a larger fascicule, which was found weeks later at the Chilean National Library. The officialist press prominently advertised and covered the event, while the oppositional press largely criticizes it and condemned it. The National TV Channel also covered the dictator’s appearance and speech at the event, which helped to fill in the gaps of the story. The Ministry of Housing and Service for Housing and Urbanism Archives had the drawings in their deposit in different versions that made up the final plan, which prepared for the event and was eventually placed into circulation.[3]

This apparently simple plan, made on a piece of cheap paper, allowed for the reconstruction of a crucial and partly forgotten episode of the dictatorship years: the ceremony of the mass distribution of property titles for almost 40,000 people, implemented by the State of Chile in the National Stadium of Santiago in September 1979. They were families that had been occupying state land for decades, and through this initiative to privatize the property, the families became confined to peripheral areas of the city. What looked like a gift ended up being an imposition, and a mode of including them in the financial and economic system of the regime. That event altered the social, historic, and symbolic image of the National Stadium, a building which for eighty years has been a place of community gathering around sports, politics, and cultural activities, without forgetting that its most violent occupation was in 1973 when it was transformed into the largest detention center and torture camp in the country after de coup d’etat during 58 days.

The event was the largest juridical and administrative operation in Chile’s history, and only possible to execute under the unlimited force of a military dictatorship. It announced a new housing policy that transformed the nature of social housing, which until that moment was conceived as an inalienable right, became a consumer good, dependent on the savings capacity of potential owners. From then on, not the State but the market would regulate land costs and housing construction. In this way, the event in the spring of 1979 also announced the creation of a new urban subject: from prolétaire to propriétaire the notion of the dweller was transformed to that of the housing debtor and potential future owner.

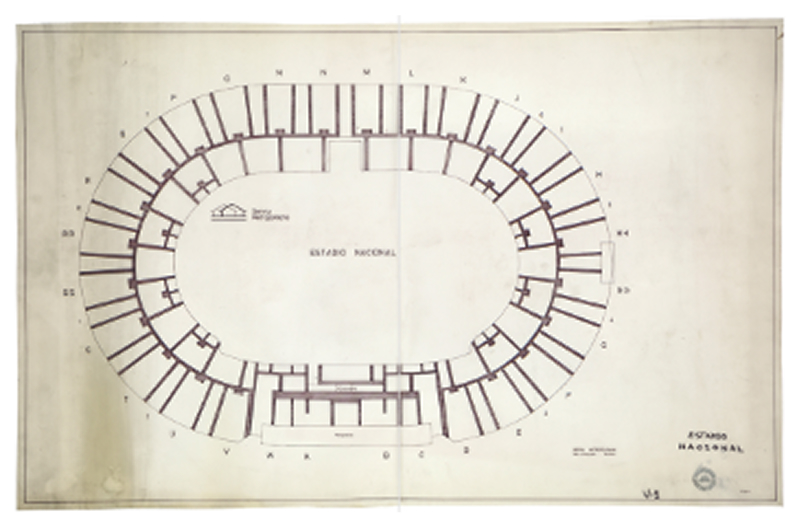

The drawing of that plan not only functioned as a subjectivation machine but became a draft of the configuration of a city. The subject and the city were inextricably produced as if one were to craft the other. Unraveling this drawing's geopolitical strategy need to carefully delineate the multiple arrows that created an ensemble out of these connections. The drawing operated as an archeological reverse of history or forensic deconstruction, that while operating through images, intentionally recognized gaps—spaces that cannot be filled with architecture alone but requires alternative evidence such as photographs, texts, ideas, clippings, and similar materials. This follows Foucault’s archeology of knowledge when he said: “history in its traditional form, under took to 'memorize' the monuments of the past, transform them into documents, and lend speech to those traces which, in themselves, are often not verbal, or which say in silence something other than what they actually say; in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments.”[4] (Figure 3-4)

Figure 3: (left) Stills from the reportage broadcasted on September 29, 1979 on TVN (National Television of Chile). (Right) Savings book for housing installments, Minvu.

Figure 4: Planta del Estadio Nacional Source / Fuente: Archivo Serviu RM.

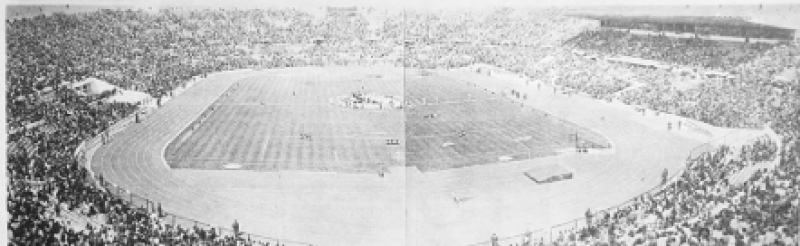

The different archival elements (object, drawings, text, film) gradually came together to form a rich milieu that, amid way fiction and evidence, functioned as a self-critical device. The stadium, having undergone countless occupations and which today seemingly functions innocently in its original role as a sports stadium, is subjected to a conjectural ruination of an economic model, allowing it to speak for itself. The drawing has finally reconnected the building with its broader critical past.(Figure 5-6)

Figure 5: La Tercera Newspaper, 30th of September 1979. Biblioteca Nacional Archive.

Figure 6: Chile Pavilion in the 16th Venice Biennale. Photography by Gonzalo Puga.