Few works crystallize the often complicated and fraught experience of homecoming in the Caribbean as viscerally as Aimé Césaire’s magisterial long poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land). Profoundly burdened by the baggage of the politics of cultural assimilation that characterized the French colonial project in the Caribbean, the poet’s return from Paris to his native Martinique is, initially, an inhospitable homecoming. The poem tracks the native’s destabilizing encounter with the ugliness and detritus of an island homeland that had been otherwise abandoned, excluded, and marginalized from its French metropole. Confronted by a grim reality shaded by the colonial gaze, Césaire’s Cahier charts the poet’s re-acclimation, rebirth, and radical embrace of this home, notwithstanding its wounded and scarred exterior—in what amounts to a project of affective, cognitive, and cultural decolonization. Ultimately, Césaire envisions this homecoming as a return to a black self, an experience famously encapsulated in his coinage of the term négritude—a poetic re-appropriation and revalorization of the pejorative négre that had been abjected by Europe. This return to a black self, Césaire writes, would suture the “umbilical cord” that had tethered the Caribbean to its primordial home, Mother Africa.[1] Yet, although Césaire viewed Africa as the originary source of an affirmative blackness, it is in Haiti that he located the blueprint of a revolutionary and defiant black self-reclamation.[2] As he declares midway through Cahier, “Haïti où la négritude se mit debout pour la première fois et dit qu’elle croyait à son humanité” [“Haiti where negritude stood up for the first time and said it believe in its humanity”].[3] Thus, in Césaire’s cultural politics and aesthetics of négritude, Haiti’s constitutional declaration as a black sovereign state represents a pure, uncontaminated blackness that metonymizes a geopolitically distant Africa.[4]

While Césaire’s theory of négritude has been charged with reifying a racial essentialism that weakens its anti-colonial impulse, Cahier’s legacy to contemporary Caribbean creative expression remains integral. As J. Michael Dash avers, Césaire has been invoked “to symbolize the affirmation of home, as an unambiguous foundation for the assertion of difference in the face of a deterritorializing incorporation into the colonial system or transcendent values of the west.”[5] Césaire’s poetic homecoming has provided the rhetorical and aesthetic grounds for Caribbean writers and artists to imagine new and alternative modes of diasporic home—and place—making in an era marked by displacement and dislocation.

In this short reflection, I consider the aesthetic re-significations of Césaire’s vision of coming home to blackness, as a re-turn toward Haiti, considering the domestic uncertainty facing Haitians in Hispaniola today. I write this in the aftermath of the Dominican Republic’s announcement on October 2, 2024, the eighty-seventh anniversary of the 1937 Parsley Massacre, that it would deport thousands of Haitians back “home.” This move follows the Dominican state’s highly-publicized legislation of the deportation and denaturalization of Haitian migrants and Dominican citizens born to Haitian parents, respectively, formalized in what became infamously known as La Sentencia.[6] As scholars have shown, these anti-Haitian policies are historically rooted in a contentious racial-juridical narrative mobilized by the Dominican Republic to differentiate its Hispanist cultural character and “constitutionally white” legality from Haiti’s “African” heritage and black sovereignty.[7] In turn, Dominican national discourse has viewed the proximity of Haitian migrants to Dominican citizens as a racial, cultural, and moral contaminant. At the same time, there has been a resurgence of Dominican voices that have patently challenged the state’s anti-black discourses and, with them, misconceptions about Dominicans’ identification as black.[8] My interest here lies in elucidating how representative aesthetic practices centered on Afro-descendant Dominican subjects mediate this disjuncture between, on the one hand, anti-Haitian and anti-black policies and, on the other, black self-affirmation.

In particular, I demonstrate how Césaire’s vision of coming home to a blackness via Haiti is complicated and “detoured” in Dominican cultural production. I take as a case study the 2022 film Bantú Mama, written and directed by Dominican filmmaker Iván Herrera in collaboration with French actress, singer-songwriter, and screenwriter Clarisse Albrecht.[9] Bantú Mama features Albrecht in the lead role of Emma, a French national of Cameroonian heritage who finds asylum—and, in the process, herself—among a community of orphaned youth in inner city Santo Domingo. Detained by the Dominican police on drug trafficking charges, a fortuitous collision with a car overturns the police van transporting Emma, allowing her to escape by swimming across the Isabela River. Marooned on the shores of the capital city’s Capotillo neighborhood, shown later in the film to be “el barrio más peligroso de Santo Domingo” [the most dangerous neighborhood in Santo Domingo], Emma is found and rescued by two parentless siblings, T.I.N.A. and $hulo, teens who represent many of the country’s young victims of racialized policing, criminalization, and carcerality.

The heartwarming film follows Emma’s evolution from an outsider to a reluctant surrogate [African] mother to T.I.N.A., $hulo, and their youngest brother, Cuki, in the absence of their deceased birth mother and incarcerated father. Emma’s short-lived time in Capotillo allows her to reaffirm both her African identity as a French mixed-race woman who, likewise, has been orphaned from her African heritage by the cultural politics of French citizenship and by her similarly absent parents. In the process, she educates the young trio about Africa and their shared diasporic heritage. The film captures this tenderly in a scene where Emma shows T.I.N.A. different ways of wrapping her hair, in the style of West African women, depending on the mood or setting (Figure 1). Overall, Emma’s detour in the Dominican Republic seems to have a self-affirming “Africanizing” effect on her, as her maternal relationship to siblings T.I.N.A., $hulo, and Cuki deepens.

As it explores Emma’s awakening, Bantú Mama simultaneously weaves another, less explicit thread that suggests a connection between Emma’s predicament and that of Haitians in the Dominican Republic. Notably, there are several key moments in the film where she is momentarily mistaken for being Haitian—and where this mistaken identity further threatens her already uncertain situation in Capotillo. In these moments, it seems as though Herrera and Albrecht want to make a connection between Haiti and Africa in terms reminiscent of Césaire’s black homecoming.

In it its revalorization of a blackness that originates in Mother Africa, as the film’s title patently suggests, Bantú Mama not only rehearses a post-Césairean ethos, but it also reflects a turn in more recent Latin American cinema that, in the last decade, has given increasing prominence to stories by and/or about black and Afro-descendant people. Herrera and Albrecht’s film follows other black-centered Latin American films such as Colombia’s Chocó (2012), Venezuela’s Pelo malo (2013), and Mexico’s highly contentious La Negrada (2018)—to name a notable few among a fledgling catalog of contemporary Afro-descendant-focused cinema.[10] For better or worse, in their depictions of the lived experience of black and Afro-descendant communities in Latin America, these films have attempted to revise Latin America’s foundational discourse of mestizaje and its attendant myth of racial democracy, whose validity and functioning, as I have discussed elsewhere, necessitate the severing and absorption of blackness into the Latin American body politic.[11] According to Tanya Katerí Hernández, these discourses work ancillary to “immigration law and customary law” that regulate race through the differential exclusion of Afro-descendant subjects as citizens of Latin American nations.[12] Thus, as recent Latin American and Caribbean literature, film, and art make clear—and, as I discuss in my recently released book, Caribbean Inhospitality: The Poetics of Strangers at Home, the meaning of “home” is very much entangled with the racial aesthetics of citizenship legality.[13] For example, Jorge Solano’s La Negrada, widely and justifiably condemned by Afro-Mexicans for reproducing misogynoir and racist stereotypes about black Mexicans, rightly depicts how the discourse of mestizaje not only defines the narrative of Mexican nationhood but, also, reduces nationality to a racial essence. In one scene, the film’s Afro-descendant protagonist is forced to show her papers and recite the Mexican national anthem because her black phenotype presumably belies the governing equation of Mexican citizenship with an essential and visible mestizaje.[14]

In a similar manner, Bantú Mama offers a subtle commentary on how legal status and personhood are bound up with a dubious politics of skin—and, more broadly, phenotype—in the Dominican Republic. The film touches on the vicissitudes of Emma’s uncertain juridical status, in light of Haiti’s figural association with fugitivity in Caribbean thought, on the one hand, and Haitians’ very real and present precarious status in the Dominican Republic’s national and legal discourses, on the other. Emma’s forced detour in Santo Domingo witnesses her transformation from a French tourist to a criminal, a maroon, and, ultimately, an undocumented refugee, having had her passport confiscated by the police during her arrest. Cut off from the succor of the French government, in a neighborhood located at the margins of Dominican society, Emma’s movement through different categories of illegality and fugivity recalls the cultural aesthetics of marronage that Césaire envisioned as an antidote to French assimilation—and that his intellectual heir Édouard Glissant identified as constitutive of Caribbean creative expression. Likewise, watching the devolution of Emma’s legal status, one gets the sense that her story might potentially serve as both an allegory and moral indictment of the Dominican state’s racialized and anti-black violence against Haitian migrants, especially, migrant mothers and Dominican citizens of Haitian descent, who have been targeted by a highly publicized policy of deportation and denaturalization.[15]

It seems, however, that Herrera and Brecht do not allow Bantú Mama to fully coalesce into an allegory of either Haitian migrancy or homecoming shared between Dominicans and Haitians. Rather, Emma’s story is a figuration of a detoured Haitianness. Here, I am thinking alongside Édouard Glissant, who conceptualizes what he calls the Détour as the condition of a people whose actualization as a self-determined community (a nation) has been blocked by a system of domination that remains occluded and displaced elsewhere (“ailleurs”).[16] In Bantú Mama, however, the detour works as a figure of speech, somewhat similar to a metonym, whereby what might appear to stand-in concretely for Haitianness is simultaneously displaced and occluded by Emma’s more tolerable embodiment of a blackness located in a distant, imagined Africa. This figural detour allows the film to toy with the specter of Dominicans’ affective and embodied kinship with Haitians, only to interrupt Haitians’ actualization as neighbors, rather than blackened criminals in the nation’s cultural and political imaginary. I draw our attention to four crucial scenes in which the film insinuates Emma’s symbolic relationship to Haitianness only to detour from it.

First, Bantú Mama sets the terms for this detoured encounter with Haitianness at the beginning of the film. In an intimate scene, Emma has her hair braided by a Haitian worker at the Dominican resort where she is staying prior to being arrested. Although the nameless braider’s origin is never explicitly disclosed, it is inferred in a telling conversation that reveals Herrera and Albrecht’s desire to connect Haiti to Africa:

Emma: C’est jolie ça chanson. [That’s a nice song.]

Braider: C’est une chanson de chez moi. [It is a song from my homeland.]

Emma: Ça fait longtemps que tu habites ici? [Have you lived here long?]

Braider: Il y a deux ans…Et toi, tu viens d’où? [It’s been two years. And you, where are you from?]

Emma: De France. Et de Cameroun. [From France. And from Cameroon.]

Braider: J’aimerais bien aller en Afrique un jour. [I would love to go to Africa one day.]

Emma: Moi aussi. [Me too.]

The scene situates the braider’s Kreyòl-inflected French in a contrapuntal relation to Emma’s metropolitan voice. When giving an account of her provenance, Emma amends her initial answer (“from France”) after a quick yet noticeably meditative pause to add “from Cameroon.” Emma’s encounter with Haitianness provokes the first of a series of awakenings to her African self. The conversation between Emma and the Haitian braider reveals a shared longing for a distant Africa that neither of them have visited or seen, notwithstanding Emma’s assertion that she is from Cameroon. Emma’s dual affirmation that she is as both French and Cameroonian works to disrupt what, earlier in the film’s glimpse of her life in Paris, are dark-skinned West African men’s identification of her as “exotique,” a word etymologically derived from the Latin and ancient Greek words for “foreigner,” more than likely because of her lighter, possibly mixed-race appearance. Presumably, in the Dominican Republic, Emma can inhabit and embody “Africa” in ways that are not available to her in France.

Yet “Africa”—as an origin, a home, and a fantasy—does some heavy cognitive and affective work in Bantú Mama, perhaps in terms that recall and exceed its centrality in négritude. As Achille Mbembe has argued, Africa is both a place and a repository of racial fantasies that allows the West to “give a public account of its own subjectivity” as the locus of Reason.[17] Importantly, Africa typifies a fantasy that revolves around what Mbembe has called “Black Reason”—a “collection of voices, pronouncements, discourses, forms of knowledge, commentary, and nonsense, whose object is things or people ‘of African origin.’”[18] While “not all Africans are Blacks,” Mbembe notes, the historical and extractive process of colonialism gives “Africa” a body—that “raw manifestation” of an ontological difference—that conjoins “Africa” to “Blackness.”[19] In Bantú Mama, however, “Africa” becomes hesitantly conjoined to Haiti in order to metonymize their shared association with blackness in Dominican political discourse. The film suggests this linkage in another scene where Cuki asks Emma if “¿Camerún queda en Haití?” [Is Cameroon in Haiti?] In turn, Emma responds with a gentle corrective, stating that “Camerún es otro país del otro lado del Atlántico, en África” [Cameroon is another country on the other side of the Atlantic, in Africa]. Given his young age and economic status, Cuki would not have traveled beyond the confines of his community. His rather innocent question is informed by his social education, received from Dominican national discourse, which would have taught him that a black, French-speaking person—even one who looks like him—must, by default, be Haitian because Haiti (and Haitians) is radically foreign to and, therefore, symbolically distant from the Dominican Republic, just like Cameroon.

When T.I.N.A. and $hulo take Emma home after finding her washed ashore, they similarly interrogate her origins. $hulo asks, “¿Tú eres haitiana?” [Are you Haitian] to which T.I.N.A. counters, “Pero ella no parece haitiana” [But she doesn’t look Haitian]. The key scene subtly unmasks the contradictions within Dominican political rhetoric and national discourse as they concern both Haitians and Dominicans. Marking Emma’s transition from tourist to fugitive, $hulo’s question is the film’s clear signpost of the implicit—and, more often than not, explicit—association between illegality and criminality and Haitianness in Dominican cultural and political discourse. Notably, this association is consolidated in the canonical essay La isla al revés, in which former Dominican head of state and writer Joaquín Balaguer attributes to Haitians an inherent moral degeneracy that is rooted in their fundamentally migrant—and, therefore, unstable—character.[20] When T.I.N.A. corrects $hulo’s misidentification of Emma as Haitian, however, it is likely because Emma’s mixed-race phenotype allows her to be similarly misread or “pass” as not quite Haitian.[21] For, within the Dominican political and cultural imagination, Haitiannness has been imagined and fantasized as a biologically undiluted and, therefore, a phenotypically identifiable or, otherwise, darkened blackness—the blackest of black.

In a fourth scene, after T.I.N.A. has taken Emma to meet a Dominican lawyer-cum-trafficker who will arrange for her escape with fake papers, a national police officer detains Emma while she is strolling in Capotillo. The police officer asks Emma for her papers. When she reluctantly claims she has left her papers at home, the officer demands her cédula, the official government identification card issued to Dominican citizens and residents by the state. When she is unable to present either, she is placed in the back of a truck—alongside other people who are, more than likely, Haitians (figure 2). First introduced and mandated for all Dominican citizens and residents under the government of Trujillo in the 1930s, the cédula allowed the state to monitor where people moved. Most importantly, it also allowed the state to determine who was Dominican and who was Haitian by noting the holder’s race (based on skin color) on the card. The cédula’s institutionalization is so deeply entwined with the anti-Haitian policies that culminated with the 1937 massacre of Haitians mandated by Trujillo, such that police’s demand to Emma would, for viewers acquainted with its history, undeniably place Emma as a stand-in for Haitian migrants. Nevertheless, the film, once again, interrupts the critical possibilities of this association: the lawyer-cum-trafficker, who happens to be in the vicinity, intervenes on Emma’s behalf and obtains her release with a bribe to the officer. The Haitians in the truck, however, do not fare as well, as they remain en route to an uncertain future.

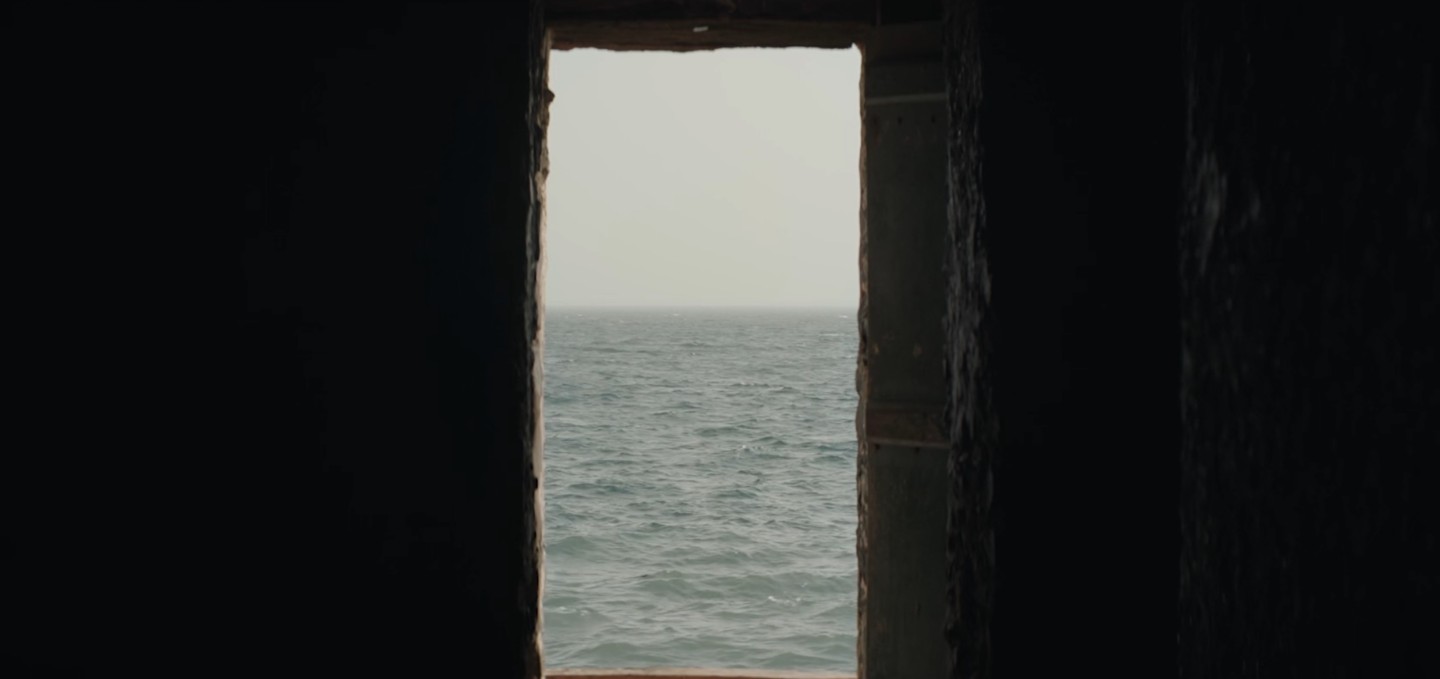

Emma ultimately makes her escape in the cover of night on a yola, a scene that rehearses the real-life and often tragic circumstances of Haitian and Dominican boat people—refugees and undocumented migrants who risk their lives crossing the Caribbean Sea in open vessels and make-shift rafts, as captured in representative Caribbean literature, visual art, theater, and media.[22] She leaves with Cuki, whom T.I.N.A. has asked her to take so that he can have a hopeful future beyond the inescapable carcerality that awaits all young black males in Capotillo. In the film’s final sequence, the camera transitions to a view of Gorée Island, Senegal and, then, to the historic Door of No Return in the island’s Maison des Esclaves (figure 3), the house where enslaved Africans were held before they passed onto ships that would transport them to the Americas. Rather than re-turning to the Cameroonian homeland she had previously claimed, Emma choses to make her home alongside Cuki in Senegal—the home of négritude’s key African expositor Léopold Senghor.

How, then, do we make sense of these constant relations and dissociations, or what I have called detours from Haiti and, broadly, Haitianness in Bantú Mama? In my estimation, Emma’s disidentificatory presence in Bantú Mama—as simultaneously possibly and not Haitian—allows the film to only tentatively intervene on both the predicament of Haitians and the question of blackness in the Dominican Republic. Cuki, a son of the Dominican Republic who will live out his formative years in Senegal, represents the hope of a diasporic blackness that, nevertheless, cannot ground itself in the Dominican Republic—at least, not now. Emma’s role, on the other hand, serves to demystify anti-Haitian tropes in their ontological relation to black abjection. The film, thusly, becomes about Emma’s homecoming to a [black] African self, yet it leaves unresolved the Dominican state’s ongoing eviction of Haitian migrants and naturalized Dominican citizens of Haitian-descent from the very place they call home. Emma must return to Senegal—in the same way that Haitians and Haitian-descendant Dominicans must return to Haiti—to mother a blackness that the Dominican nation is not yet ready to nurture in the film’s imaginary.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3