This short essay focuses on artworks by Latin American women that probe boundaries using body parts and fluids. I argue –paradoxically–that in pieces by experimental artists after the 1960s, body fragments such as cells, the mouth, the eyes, and the vagina, as well as bodily fluids such as menstrual blood stand not only for an uncontrolled and reimagined body, but a reconceptualized social body. The works I include are only a fraction of what exists, and they should be thought of as an invitation to explore the powerful imaginary of a rich iconography of the female body.

I would like to begin with the ground zero of the body, which is its cells. Brígida Baltar (Brazil, 1959-2022), while battling cancer during the last year of her life, created a series of embroidered pieces such as Os Hematomas (Hematomas), 2016 (Figs. 1 and 2) which render diseased cells as beautiful and simultaneously ominous irregular amoeba shapes.

Fig. 1. Brígida Baltar, Bruises [Os hematomas], 2016.

They are presented in diverse colors, such as deep red and blue, and with one or more nuclei, floating on a embroidered surface of deep mauve. Since the mauve area does not reach the lower part of the piece, two cells float on a raw white fabric, disembodied as their body dies. Baltar died of Leukemia but this series stands as a beautiful examination of illness at a cellular level, through a materialization of the body which is both philosophical and subjective. Adriana Varejão (Brazil, 1964-) has explained that she is “(…) an artist who found her roots in the baroque, and it is interesting to think about how baroque architecture deals with the notion of interiority.”1 Stressing how, contrary to modern architecture, Baroque interior spaces do not relate to their façades or exteriors, but are lieus of timeless interiority. In works such as Tilework with Horizontal Incision, 1999, or more recently Brasilis Ruin, 2021 (Fig. 3) the fleshiness of raw meat cracks and overflows the tiled surfaces of walls and columns. The violence embodied by the flesh breaking the tiled walls, thus recreating Baroque environments such as baths and saunas, for the artist should not be interpreted simply as the violence of the colonizers. Inspired by Severo Sarduy’s book Written on the Body, 1989, the flesh and entrails that emerge from these surfaces are more ambiguous and open-ended as spaces of fiction that may be closer to notions of eroticism as found in Sade and Bataille, in that the disruption of the flesh may have a double meaning or a dialectical interplay between violence and pleasure, between power and control. Also, “to kick out the ghosts that live inside these structures—deep inside—and let out that scream that comes out of the walls.”2

Fig. 3. Adriana Varejão, Brasilis Ruin, 2021.

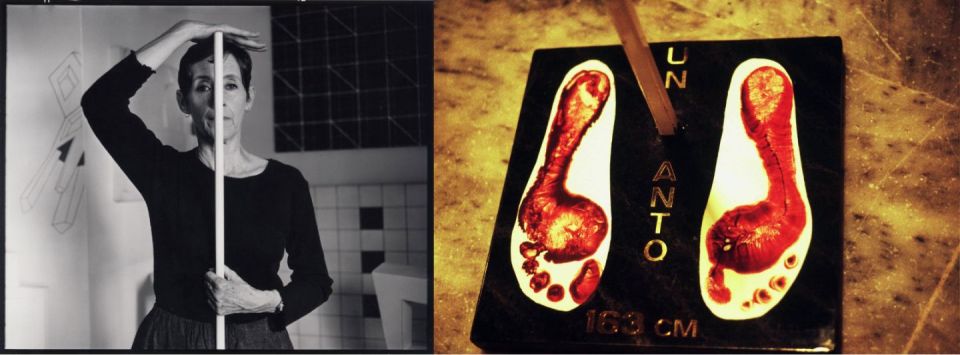

The overflowing of the flesh inhabiting the space of architecture and the history of the body, brings to mind Venezuelan conceptual and performance artist Antonieta Sosa (Venezuelan,born in the US, 1940-2024) and her creation of the anto, a term that stands for the abbreviation of her first name. The anto is a measurement system based on the height of her 163 cm body, which the artist employed as a conceptual tool to create objects associated with daily life such as chairs and stairs. These items were used in her home, as props for her performances, and as sculptures in their own right, thus blurring the line between art and life, between the body and the external structures that contained and determined her movements and actions. Sosa stated that the anto is “an imaginary line that passes through the center of my body. The idea is to measure the world with a female body, with my body. (…) I suspect that measurements were invented by men and that behind them lurks some manipulation of power. (…) I seek to create my own measurement that is feminine and to remove myself from systems of power.” 3 Importantly, by shaping these objects within the scale and manifest female genderness of her body, Sosa counters the predetermined structures of body politics that shape our daily lives, and thus the implicit though apparently benign violence embedded in the estranged architecture of our everyday acts such as sitting, walking, and resting, and thus activating their potentiality for imagination, sensuality, and emancipation (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. Antonieta Sosa, UN ANTO= 163 cm, a la medida de mi cuerpo, ni un milímetro más ni un milímetro menos.

Fig. 5. Antonieta Sosa, UN ANTO= 163 cm, a la medida de mi cuerpo, ni un milímetro más ni un milímetro menos.

Though artists have explored a breadth of body parts, I would like to focus specifically on two: the mouth and the vagina, for their erogenous and conceptual potentiality. As Claudia Calirman argues, many women artists in Brazil starting in the 1960s and 70s, deployed the wide-open mouth as an expression of political defiance both against Brazil’s dictatorship (1964–1985) as well as patriarchal prescriptions over the female body.4 Brazilian artists have been deeply influenced by the notion of anthropophagy, after Oswald de Andrade’s Manifesto antropófago (1928), in which cannibalism as a pre logical act becomes a metaphor for the ingestion of colonial culture to be reconstituted in a syncretic Brazilian culture where the Indigenous and African are also constitutive. Anthropophagy is not a benign term, given its implications of strain–whether colonial, societal, sexual, etc.killing, and devouring, but it also embodies sensuality and reconstitution. In the super 8 film by Anna Maria Maiolino (Brazilian, born in Italy, 1942 - ) In-Out (antropofagia), 1971, we see a sequence of close ups of a succession of two mouths–one female and one male–gesticulating while at first making no sound and subsequently mutter nonsensical utterance and grunts. This is followed by menacing grinning teeth, ending with a mouth holding an egg, and thus no longer able to emit any sound while embodying the potentiality enclosed within the egg with its fertility and nutritional attributes. This piece is abject, seductive, and sensual, and exists at the intersection of the pre linguistic and irrational, the desire to communicate, and the existential emergence of a new self in the context of Maiolino’s exile and encounter and integration into Brazilian culture. Lygia Pape (Brazil, 1927-2004) Eat Me, 1975, also echoing In-Out, is an experimental film that consists of a sequence of close ups of a male mouth that covers the entire screen. The slightly ajar lips are glossy, plump, and pink, with a lustrous mustache , creating an unstable perception of gender. Objects sit unsteadily, about to be ingested on a tongue, while a seductive female voice repeats the terms “a gula ou a luxúria” (gluttony, lust). In her essay on this work5, Pape discusses how the inner and the outer spaces merge and disappear, becoming continuous, highlighting the sensorial as a form of consciousness and knowledge, embedding this work in the ethos of her Objects of seduction, which are visceral, insubordinate, and bodily. Eat Me is a film to be projected on a large screen so that the mouth beckons us, threatening to swallow us with its anthropophagic nature, not only highlighting the lips and body–also our own–and its fluids, but also recalling an enormous anus, completing the cycle of consumption–swallowing, devouring–and excretion.

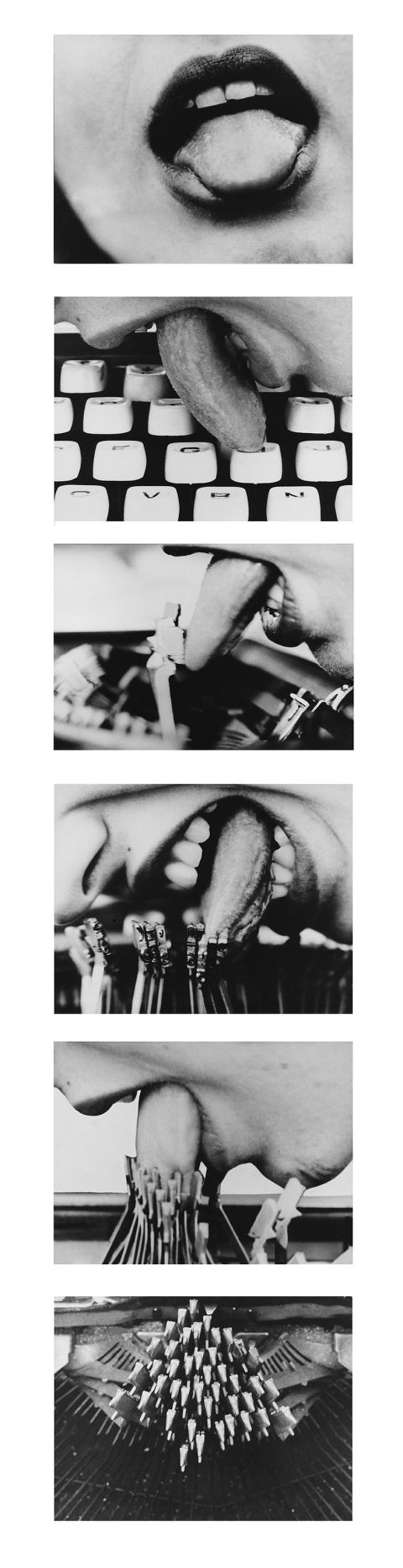

Lenora de Barros, Poema (Poem), 1979, (Fig. 6) leans into the sexual and gestating potential of the tongue. de Barros is both a poet and a conceptual and performance artist, and this work was born out of an intent to imagine/conceptualize how language, specifically poetic language, is born. The artist had a breakthrough when she envisioned her tongue directly fertilizing her typewriting machine, an act of making love to the keys, transforming the tongue into an active “male” organ, thus exercising a sort of union between her female and male self as well as between her tongue and the machine.

Fig. 6. Lenora de Barros, Poema (Poem), 1979/2014.

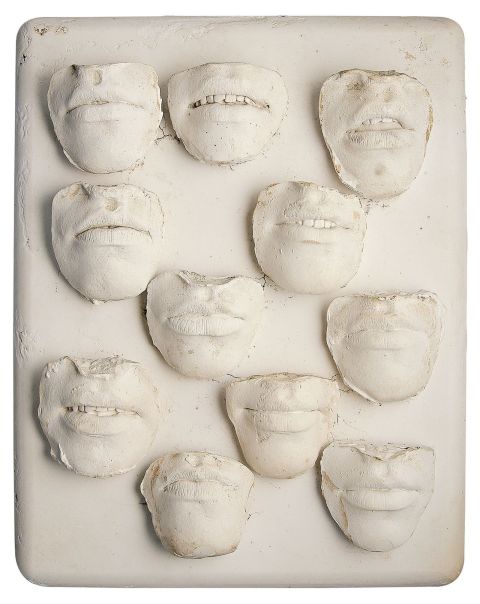

Here writing becomes a bodily act, not only thought in the head and exercised through the hand, but a sensual form of materialization of language, both poetic and artistic. De Barros has continued to elaborate both on language and the tongue, increasingly radicalizing their representations by presenting an overextended tongue crossed by a long spine, as if supporting not only the body but the conceptual and vital existence of her whole being. Estudo para facadas (Study for Stubs), 2013 is a photograph which is repeatedly pierced by a knife; and in a separate work, a tongue is bitten by its teeth, unable to free itself. All these works embody an existential liveliness and a will to engender meaning, while also revealing the violence of their oppression. (Amelia Toledo’s (Brazil, 1926-2017) Sorriso do menina (Girl’s smile), 1976, (Fig. 7) is a sculptural piece made during the dictatorship from her series of casts of fragments of bodies such as mouths, teeth, ears, hands, and fingerprints. Sorriso do menina is a wall piece that includes the plaster cast of several smiling mouths on a white surface

Fig. 7. Amelia Toledo, Sorriso de menina (Girl’s smile), 1976.

This piece, as well as As paredes tem ouvidos (The walls have ears), 1975, a single cast of an ear embedded on the wall, have political implications, as they were made during the dictatorship. Since these parts are disembodied, they suggest fragmentation in the context of repression and the violence of totalitarianism. I end this section with the photographer Graciela Sacco, (Argentina 1956-2017). Her series Bocanada, 1993–2014, consists of photographs of open mouths printed in heliograph in sepia tones and glued to different surfaces, from matchboxes and floors to street walls. These images function politically, as they invade the streets as silent screams, not only symbolizing hunger in the marginalized sectors of society, but notably, the inability to communicate thoughts and desires.6 Similarly to Toledo, Sacco, explored other body parts, such as eyes, in Entre nosotros (1995-2014) realized in parallel to Bocanada. (Fig. 8) For the 2001 Venice Biennale, she adhered 10,000 images of pairs of eyes throughout the city on walls, stairs, benches, creating an uncanny interplay of seeing and being seen, suggesting not only surveillance but the ghostly presence of history and the many bodies that have dwelled within the city. Mouths and eyes occupy city walls, disembodied but shaping in their fragmentation a haunting corporeal urban landscape, a sort of testament of human existence.

Fig. 8. Graciela Sacco, De la serie Bocanada, interferencia urbana en Rosario, 1993.

The iconography of the vagina had an important place in feminist art in the 1970s and 1980s in the US but was not as common in Latin America as an overt motif. It is nevertheless present, particularly in relation to the use of menstrual blood. It is meaningful to recall Marta Palau’s (Mexican, born in Spain, 1934-2022), Llerda V, 1973, which is part of a series of soft textile sculptures alluding to large vaginas. Made with Spanish jute and cotton, with an imposing scale of 160 cm, that hung elevated floating in space, it creates a sort of feminization and erotization of the space where it is located. These are unruly sculptures because of their woven, organic material made from fibers traditionally associated with crafts and basketry instead of large-scale art pieces. They counter both the geometric rationality of architecture with an organic bodily femininity, as well as disturbing hierarchies that marginalize women by pigeonholing textile and crafts outside of contemporary art. Zilia Sánchez’ (Cuba 1928-) Erotic Topologies from the 1970s propose an analogy between the landscape and erogenous zones, such as breasts and the vagina. These works are abstract tridimensional shaped paintings/sculptures made by stretching canvas over a wooden armature that creates protrusions in ways that recall a labia, interlocking tongues, or the contours of breasts. Some of Sánchez’s Erotic Topologies (Fig. 9) are monumental in size, and the series is painted with a delicate palette of pink, light blue, white, or gray, evoking the topography of the landscape and the body, as well as an expansive sensuality and embodied subjectivity.

Fig. 9. Zilia Sánchez, Topología erótica, (Erotic Topology), 1970.

Nuyorican Sophie Rivera’s (US, 1938-2021), series Rouge et noir (Red and black), 1977-78, are large scale photographs of toilet bowls which seen from afar resemble beautiful abstract oval shapes in pink hues. As we observe the images at a closer distance, we realize that what creates the pink hues are bloodied Tampax releasing menstrual blood. These works were exhibited in the Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 exhibition held at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles in 2017. Standing in front of these photographs with the public while delivering a guided tour was always incredibly uncomfortable, as the public felt embarrassed by the realization of what the image was. We exist as living beings, no matter our gender, because a female body undergoes the menstrual cycle marking puberty, and the rise and fall of hormones, as part of the biological cycle of fertility. Despite its universality, menstrual blood is one of the most scatological of all bodily fluids, and thus still today, a work such as Rouge et noir by Rivera reminds us that we are still unable to embody this endless elemental process that belongs to us all, bringing us together at the very inception of our existence. I would like to conclude this section with Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Colombia, 1958), 11 de marzo – ritual a la menstruación, digno de toda mujer como antecedente del origen de la vida (March 11 – ritual in honor of menstruation, worthy of every woman as a precursor to the origin of life), 1981 (Fig. 10). This is a radical performance realized at the Galería San Diego in Bogotá, Colombia to exorcize the stigma surrounding her menstruation and menstrual blood as a bodily fluid, given that she suffered painful abundant menstruations that led to embarrassing stains in her clothes and ridicule from her brothers. For this performance the artist wore menstrual pads along her body excluding her vagina and walked in the space staining the floor and rubbing her pubis against the walls, leaving marks and letting her menstrual blood leak towards the ground. For Marmolejo and the other artists in this section, the vagina and menstrual blood become the means for setting the female body free, as well as for transmuting the art space into an unruly embodied feminine universe.

Fig. 10. Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Colombia, 1958), 11 de marzo – ritual a la menstruación, digno de toda mujer como antecedente del origen de la vida (March 11 – ritual in honor of menstruation, worthy of every woman as a precursor to the origin of life), 1981.

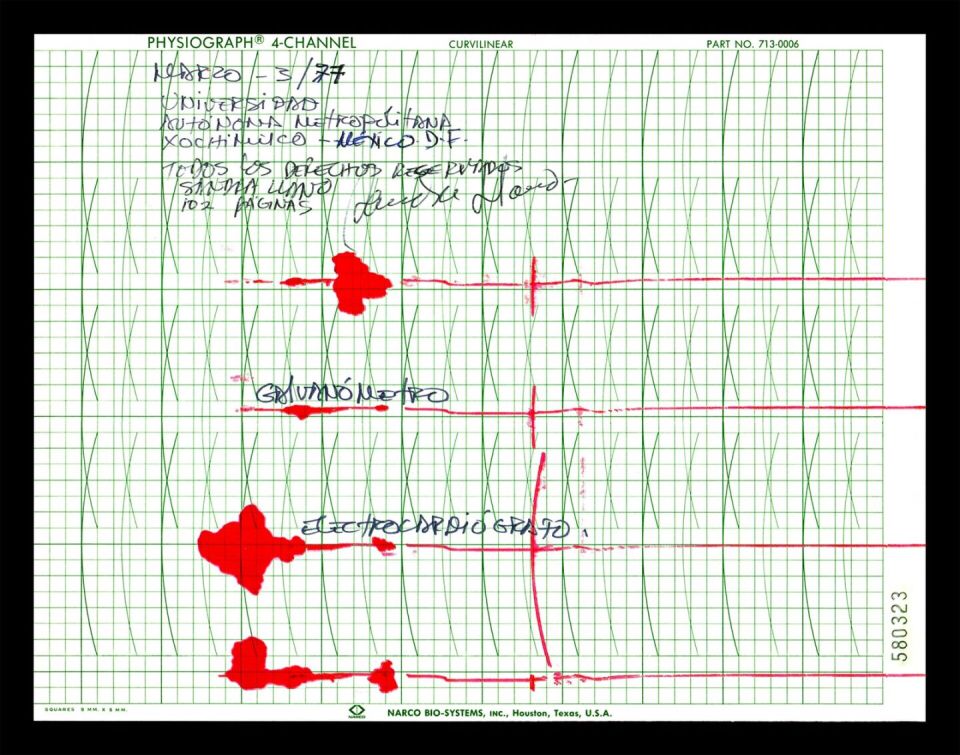

What happens when artists use the science that has shaped a taxonomy of biological and societal determinism in women’s lives to create subjective, unrestrained embodiments? Conceptual artist Teresa Burga (Peru, 1935-2021) in Autorretrato. Estructura. Informe. 9.6.1972 (Self-Portrait. Structure. Report. 9.6.1972) used science in the form of electrocardiograms, phonocardiograms, etc. to reveal every aspect of her physiological functions. This self-examination took place in the context of the Peruvian left wing Military Junta by Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1980) and Burga’s deep awareness of societal restrictions for women at the time. The Heart report within the installation included not only graphic and numerical information about her heart activity, but a red neon that lit up to the rhythm of her beating heart. Aside from its vital physiological functions, Burga’s heart in the installation, acquires a life of its own, flooding the space with a glowing red light, and the rhythmic sound of her heart, uncontrolled, overflowing the space and the spectator’s own body and senses, becoming thus the opposite of a scientific taxonomy. Leticia Parente (Brazil, 1930-1991), who had studied chemistry in Medidas (Measurements), 1976 created a similar situation to Burga’s, but this time she collected biometric data, not to further the categorization of the body, but, as André Parente -scholar and son of the artist- explains, the artist was critiquing the “theory of crime based on heredity and anthropometric data” by Cesare Lombardo7 and thus forms of control based on scientific data. Sandra Llano Mejía (Colombia, 1951-) for In-pulso (in-pulse), 1978, (Fig. 11) connected her head with sensors to an EEG-Neurofeedback machine, to read her brain in real time activity as a performative event.

Fig. 11. Sandra Llano Mejía, In-pulso (in-pulse), 1978.

For this piece Llano Mejía practiced forms of control of brain activity to modulate the brain waves, thus countering cliches of female emotionality. The machine produced encephalograms which became a form of self-portraiture that countered stereotypes associated with women self-representation as both narcissistic and sentimental. On the opposite spectrum to these artists that employ science as a strategy for disobedient embodiments, is Feliza Busztyn (Colombia, 1933-1982) and her series Histéricas (The hysterical one), from the late 1960s. Bursztyn was renowned for her sense of strange humor, and cryptic, nonsensical disconcerting responses. This dark sense of humor is best demonstrated in works such as Histérica (The hysterical one), from 1968, an abstract kinetic motorized metal sculptures that produced scraping metallic noises when activated. The uncontrolled shaking of curved metal parts, suggested irrationality and emotional uncontrollability that the artist described her as "motorized romanticism.”8 The Histérica is not only strangely abstract but industrial in nature, and given the artist’s critical and leftist leanings, the modernity that it embodies is not associated with rationality and progress, but instability and irrationality, thus also unrestrained sensuality and femininity.

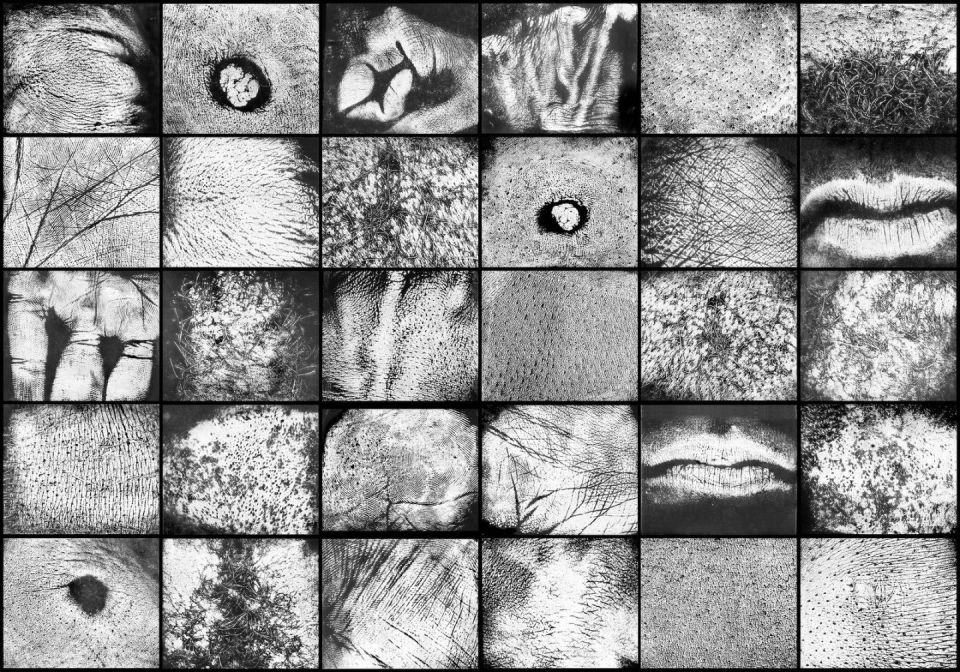

Within fragments lie the potential for an embodied and political imagination of experience. Some important examples of artists’ works include a performativity that interrogate us, such as Maria Teresa Cano’s (Colombia, 1960-) Yo servida a la mesa (Me, served as a meal), 1981, a performance by which the artist created a meal of Colombian traditional foods such as chicken with rice, custard, vegetable soufflé, cakes, white rice, and gelatin made with a mold of her head, each served on a plate, inviting the public to cannibalize it, and Con sabor a chocolate (With the taste of chocolate), 1984 for the 9th Salón Atenas of the Museo de Arte Moderno in Bogotá, cast in chocolate with molds of different parts of her body, exhibited as a fragmented female body in repose that people could eat. These pieces recall anthropophagy and reveal a close connection between sensuality and consumption, where desire and basic impulses such as hunger are awakened. Controversially, Cano turns these wants onto her own body. Ana Mendieta’s (Cuba 1948-1985), Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints), 1972, are a series of color photographs exposing different parts of her body pressed against a rectangular plexiglass sheet. We see her face, her breasts, her tummy and pubic hair, her buttocks, and her back deformed by the pressure of the rigid surface of plexiglass. These are performative photographs that reveal Mendieta’s rejection of objectification and beauty standards while simultaneously revealing the power of the female body. While conceptualizing that societal violence on women’s bodies creates an alienating fragmentation and distortion, it also suggests that the disfigurements and fractures are a form of resistance and concealment against that very violence. I will end this essay with Vera Chaves Barcellos (Brazil, 1938 -), Epidermic Scapes, 1977/1982 (Fig. 12). This monumental work of thirty enlarged images printed in an analogic process on photographic paper can be displayed on the floor or a wall. Each image was originally an ink imprint of different body parts such as skin, breasts, pubic and body hair, hands, and other fragments of the artist’s and her friends’ bodies. For Chaves Barcellos, each body and body part encompass a unique beauty that when brought together can create an infinite epidermic scape that mirrors the landscape simultaneously of the body and of nature. This is a work that reveals how our differences are beautiful and can come together, paradoxically, in a grid that does not imprison or oppress to become a whole forever expanding into a collective body that preserves the individual attributes that make us who we are: different, beautiful, imperfect, embodied, and subjective.

Fig. 12. Vera Chaves Barcellos, Epidermic Scapes, 1977